Rasdhar continues to be a reader of this world (III)

This is a continuation of the topic Rasdhar is still a reader of this world (II).

TalkClub Read 2024

Join LibraryThing to post.

1rv1988

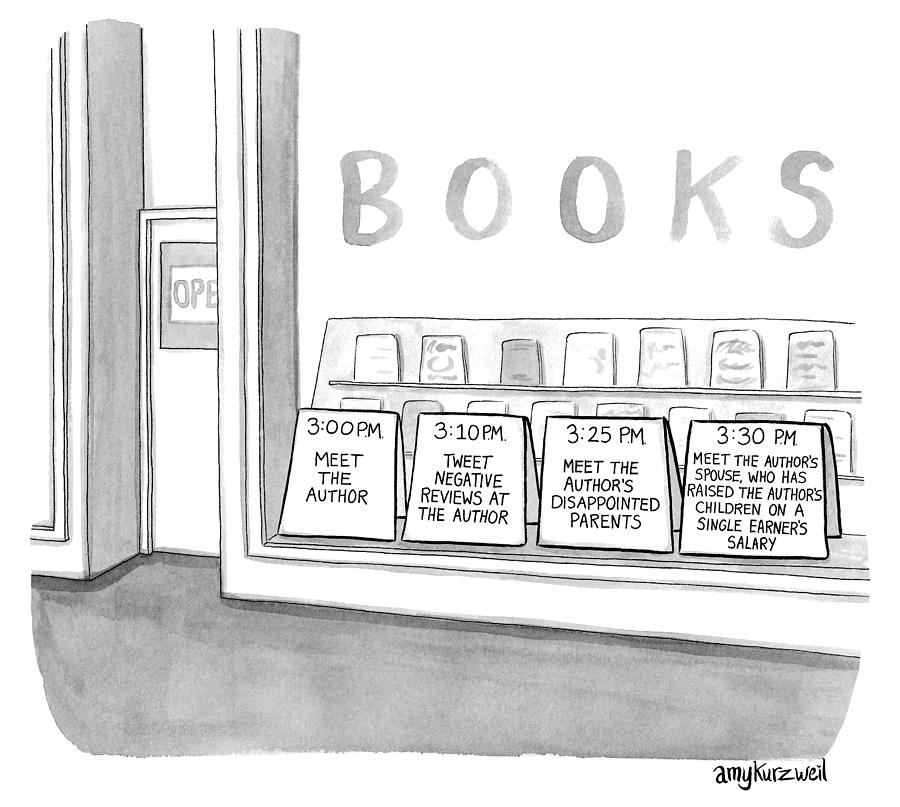

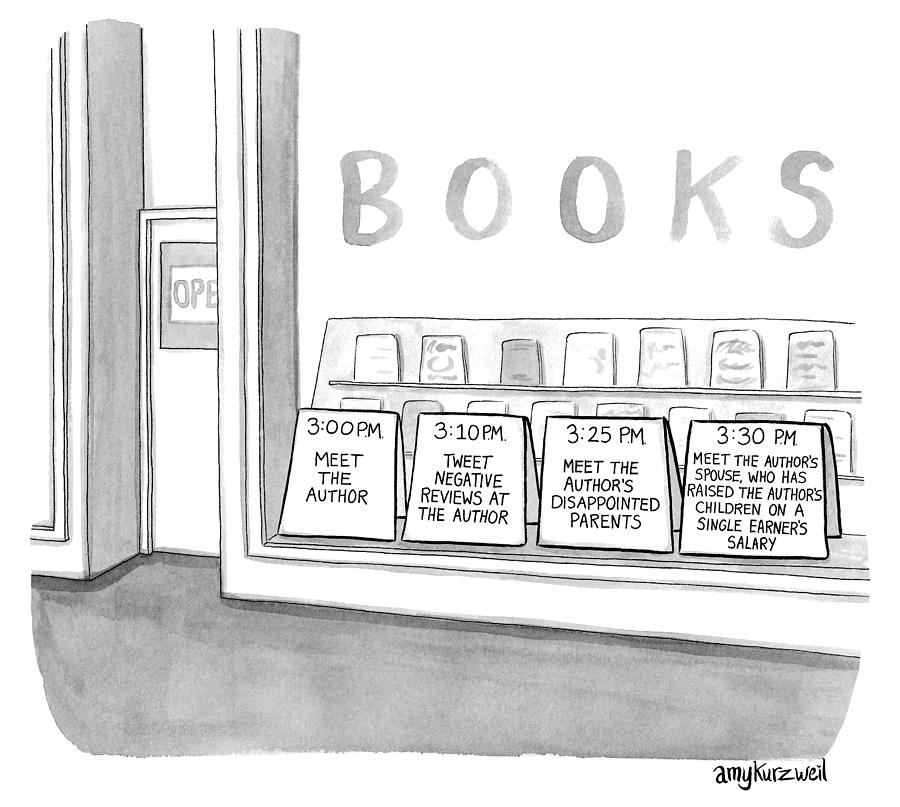

New thread, new comic, again by the wonderful Tom Gauld. This is my thread for the 3rd quarter of the year. Happy reading!

Thread for the 1st quarter: https://www.librarything.com/topic/357082

Thread for the 2nd quarter: https://www.librarything.com/topic/359708

Currently reading:

Judith Flanders - Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain (Pan Macmillan, 2024)

Helen Oyeyemi - Parasol Against the Axe (Riverhead, 2024)

Andrei Kurkov - The Silver Bone (Harper Via, 2024)

2rv1988

Books in Quarter 1

January:

1. Patricia Highsmith - The Cry of the Owl

2. Ben Aaronovitch - Whispers Under Ground Review here .

3. Magdalena Zyzak - The Ballad of Barnabas Pierkiel Review here.

4. R. F. Kuang - Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution Review here.

5. Christopher Moore - Noir and Razzmatazz Review here.

6. Emily Henry - Beach Read

7. Sebastian Sim - Let’s Give It Up For Gimme Lao! Review here.

8. Richard Osman - The Bullet that Missed Review here.

9. Kate Collins - A Good House for Children Review here.

10. Ronojoy Sen - House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Indian Democracy (reviewed on the book page).

11. Paul D. Halliday - Habeas Corpus: From England to Empire

12. Richard Osman - The Last Devil to Die Review here.

12. Eileen Chang - The Rouge of the North Review here.

February:

13. VV Ganeshananthan - Brotherless Night Review here

14. Black Coffee in a Coconut Shell (edited by Perumal Murugan) Review here

15. Chen Zijin - Bad Kids Review here

16. Anthony Berkeley - The Wintringham Mystery Review here

17. Cristina Campo - The Unforgivable, and other Writings Review here

18. Maryla Szymiczkowa - Mrs. Mohr Goes Missing Review here

19. The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries (edited by Michael Sims) Review here

20. Supriya Gandhi- The Emperor Who Never Was Review here

21. José Maria de Eça de Queirós - The Tragedy of the Street of Flowers Review here

22. Isaac Asimov - Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection Review here

23. The Forward Book of Poetry 2018 - by various poets Review here

24. Tiitu Takalo - Me, Mikko and Anikki (Minä, Mikko ja Annikki) Review here

March

25. W. H. Auden - A Certain World: A Commonplace Book (Faber and Faber, 1971) - reviewed here

26. Alex Michaelides - The Fury reviewed here

27 and 28. Keigo Higashino - Malice and Newcomer reviewed here

29. Sebastian Sim - The Riot Act reviewed here

30. Robert Thorogood - The Marlow Murder Club here

31. Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Velvet Was the Night reviewed reviewed here

32. Iris Yamashita - City under one Roof reviewed here

33. Elisa Shua Dusapin - Vladivostok Circus reviewed here

34. Yulia Yakovleva - Death of the Red Rider reviewed here

35. Laura Lippman - Sunburn

January:

1. Patricia Highsmith - The Cry of the Owl

2. Ben Aaronovitch - Whispers Under Ground Review here .

3. Magdalena Zyzak - The Ballad of Barnabas Pierkiel Review here.

4. R. F. Kuang - Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators' Revolution Review here.

5. Christopher Moore - Noir and Razzmatazz Review here.

6. Emily Henry - Beach Read

7. Sebastian Sim - Let’s Give It Up For Gimme Lao! Review here.

8. Richard Osman - The Bullet that Missed Review here.

9. Kate Collins - A Good House for Children Review here.

10. Ronojoy Sen - House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Indian Democracy (reviewed on the book page).

11. Paul D. Halliday - Habeas Corpus: From England to Empire

12. Richard Osman - The Last Devil to Die Review here.

12. Eileen Chang - The Rouge of the North Review here.

February:

13. VV Ganeshananthan - Brotherless Night Review here

14. Black Coffee in a Coconut Shell (edited by Perumal Murugan) Review here

15. Chen Zijin - Bad Kids Review here

16. Anthony Berkeley - The Wintringham Mystery Review here

17. Cristina Campo - The Unforgivable, and other Writings Review here

18. Maryla Szymiczkowa - Mrs. Mohr Goes Missing Review here

19. The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries (edited by Michael Sims) Review here

20. Supriya Gandhi- The Emperor Who Never Was Review here

21. José Maria de Eça de Queirós - The Tragedy of the Street of Flowers Review here

22. Isaac Asimov - Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection Review here

23. The Forward Book of Poetry 2018 - by various poets Review here

24. Tiitu Takalo - Me, Mikko and Anikki (Minä, Mikko ja Annikki) Review here

March

25. W. H. Auden - A Certain World: A Commonplace Book (Faber and Faber, 1971) - reviewed here

26. Alex Michaelides - The Fury reviewed here

27 and 28. Keigo Higashino - Malice and Newcomer reviewed here

29. Sebastian Sim - The Riot Act reviewed here

30. Robert Thorogood - The Marlow Murder Club here

31. Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Velvet Was the Night reviewed reviewed here

32. Iris Yamashita - City under one Roof reviewed here

33. Elisa Shua Dusapin - Vladivostok Circus reviewed here

34. Yulia Yakovleva - Death of the Red Rider reviewed here

35. Laura Lippman - Sunburn

3rv1988

Books in Quarter 2

April:

36. Emily Henry - Book Lovers (Berkley, 2022) reviewed here

37. Lyudmila Petrushevskaya - The New Adventures of Helen (Deep Vellum, 2022) translated from the Russian by Jane Bugaeva reviewed here

38. Tana French - The Hunter (Viking 2024) reviewed here

39. Karrie Fransman - The House that Groaned (Square Peg 2014) reviewed here

40. Terry Pratchett - Making Money (Doubleday 2007) reviewed here

41. Marina Tsvetaeva - Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917–1922 (Yale University Press, 2002), translated from the Russian by Jamey Gambrell reviewed here

42. Mary Roberts Rineheart - Miss Pinkerton (American Mystery Classics, 2019) reviewed here

43. Agatha Christie - Murder on the Orient Express (narrated by Dan Stevens)

44. Balli Kaur Jaswal - Inheritance (Sleepers Publishing, 2013) reviewed here

45. Ann Leckie - Ancillary Justice (Orbit 2013) reviewed here

46. Butter by Asako Yuzuki (Ecco Books, 2024, translated by Polly Barton) reviewed here

47. Graeme Macrae Burnet - Case Study (Saraband 2022) here

48. Percival Everett - The Trees (Graywolf Press, 2021) reviewed here

49. Hilary Mantel - Mantel Pieces (London Review of Books/Fourth Estate, 2020) reviewed here

50. Susan Casey - The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean (Vintage, 2024) reviewed here

51. Kalpana Mohan - An English made in India

MAY

52. Starve Acre by Andrew Michael Hurley (John Murray 2019) reviewed here

53. A Man Lay Dead by Ngaio Marsh (1934)reviewed here

54. Ministry of Moral Panic by Amanda Lee Koe (Epigram Books, 2013)reviewed here

55. Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See - Bianca Bosker (Viking 2024)reviewed here

56. Jeremy Tiang - State of Emergency (Epigram Books, 2017) reviewed here

57. Joanne Harris - Broken Light reviewed here

58. Ambedkar in London (Hurst and Co, 2022) edited by William Gould, Christophe Jaffrelot, and Santosh Dassreviewed here

59. Elena Ferrante - Frantumaglia reviewed here

60. Magda Szabo - The Door reviewed here

61. John Scalzi - The Kaiju Preservation Society reviewed here

62. Shubhangi Swarup - Latitudes of Longing reviewed here

JUNE

63. Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Silver Nitrate (Del Rey 2023) reviewed here

64. Ana María Matute - The Island (Penguin Classics, 2020, translated from the Spanish by Laura Lonsdale)reviewed here

65. Sharlene Teo - Ponti (Picador, 2018) reviewed here

66. Martha Wells - All Systems Red (2017) reviewed here

67. Donatella di Pietrantonio - A Girl Returned (Europa Editions 2019, translated by Ann Goldstein) reviewed here

68. Mari Ahokoivu - Oksi (Levine Querido, 2021, translated from the Finnish by Silja-Maaria Aronpuro) reviewed here

69. Reine Arcache Melvin - The Betrayed (Europa Editions, 2018) reviewed here

70. John Banville - Snow reviewed here

71. Doreen Cunningham - Soundings: Journeys in the Company of Whales: A Memoir (Scribner 2022) reviewed here

72. Fabulous Machinery for the Curious: The Garden of Urdu Classical Literature - edited by Musharraf Ali Farooqi (World Literature in Translation) reviewed here

April:

36. Emily Henry - Book Lovers (Berkley, 2022) reviewed here

37. Lyudmila Petrushevskaya - The New Adventures of Helen (Deep Vellum, 2022) translated from the Russian by Jane Bugaeva reviewed here

38. Tana French - The Hunter (Viking 2024) reviewed here

39. Karrie Fransman - The House that Groaned (Square Peg 2014) reviewed here

40. Terry Pratchett - Making Money (Doubleday 2007) reviewed here

41. Marina Tsvetaeva - Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917–1922 (Yale University Press, 2002), translated from the Russian by Jamey Gambrell reviewed here

42. Mary Roberts Rineheart - Miss Pinkerton (American Mystery Classics, 2019) reviewed here

43. Agatha Christie - Murder on the Orient Express (narrated by Dan Stevens)

44. Balli Kaur Jaswal - Inheritance (Sleepers Publishing, 2013) reviewed here

45. Ann Leckie - Ancillary Justice (Orbit 2013) reviewed here

46. Butter by Asako Yuzuki (Ecco Books, 2024, translated by Polly Barton) reviewed here

47. Graeme Macrae Burnet - Case Study (Saraband 2022) here

48. Percival Everett - The Trees (Graywolf Press, 2021) reviewed here

49. Hilary Mantel - Mantel Pieces (London Review of Books/Fourth Estate, 2020) reviewed here

50. Susan Casey - The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean (Vintage, 2024) reviewed here

51. Kalpana Mohan - An English made in India

MAY

52. Starve Acre by Andrew Michael Hurley (John Murray 2019) reviewed here

53. A Man Lay Dead by Ngaio Marsh (1934)reviewed here

54. Ministry of Moral Panic by Amanda Lee Koe (Epigram Books, 2013)reviewed here

55. Get the Picture: A Mind-Bending Journey among the Inspired Artists and Obsessive Art Fiends Who Taught Me How to See - Bianca Bosker (Viking 2024)reviewed here

56. Jeremy Tiang - State of Emergency (Epigram Books, 2017) reviewed here

57. Joanne Harris - Broken Light reviewed here

58. Ambedkar in London (Hurst and Co, 2022) edited by William Gould, Christophe Jaffrelot, and Santosh Dassreviewed here

59. Elena Ferrante - Frantumaglia reviewed here

60. Magda Szabo - The Door reviewed here

61. John Scalzi - The Kaiju Preservation Society reviewed here

62. Shubhangi Swarup - Latitudes of Longing reviewed here

JUNE

63. Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Silver Nitrate (Del Rey 2023) reviewed here

64. Ana María Matute - The Island (Penguin Classics, 2020, translated from the Spanish by Laura Lonsdale)reviewed here

65. Sharlene Teo - Ponti (Picador, 2018) reviewed here

66. Martha Wells - All Systems Red (2017) reviewed here

67. Donatella di Pietrantonio - A Girl Returned (Europa Editions 2019, translated by Ann Goldstein) reviewed here

68. Mari Ahokoivu - Oksi (Levine Querido, 2021, translated from the Finnish by Silja-Maaria Aronpuro) reviewed here

69. Reine Arcache Melvin - The Betrayed (Europa Editions, 2018) reviewed here

70. John Banville - Snow reviewed here

71. Doreen Cunningham - Soundings: Journeys in the Company of Whales: A Memoir (Scribner 2022) reviewed here

72. Fabulous Machinery for the Curious: The Garden of Urdu Classical Literature - edited by Musharraf Ali Farooqi (World Literature in Translation) reviewed here

4rv1988

Books in Quarter 3:

JULY

73. Magdalena Zyzak - The Lady Waiting (Riverhead, 2024) reviewed here

74. Lucy Foley - The Hunting Party (Harper Collins, 2019) reviewed here

75. Lucy Foley - The Midnight Feast (William Morrow, 2024) reviewed here

76. Judith Flanders - Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain (Pan Macmillan, 2024) reviewed here

77. Lee Geum-yi - Can't I Go Instead? (translated from the Korean by An Seonjae, Tor Publishing Group, 2023) reviewed here

78. Danielle Arceneaux - Glory Be (Pegasus 2023) reviewed here

79. Elizabeth Macneal - The Burial Plot (Picador 2024) reviewed here

80. Helen Oyeyemi - Parasol Against the Axe (Riverhead, 2024) reviewed here

81. Shari Lapena - Everyone Here is Lying (Books on Tape, narrated by January LaVoy, 2023)

82. Andrey Kurkov - The Silver Bone (Harper Via, 2024, translated from the Ukrainian by Boris Dralyuk) reviewed here

83. Peter Swanson - A Talent for Murder (Harper Collins, 2024. Audiobook, narrated by several people). reviewed here

84. Sarah Perry - The Essex Serpent (Serpent's Tail, 2016) reviewed here

AUGUST

85. Zhang Yue Ran - Cocoon, translated by Jeremy Tiang (World Editions, 2022) reviewed here

86. The Best American Mystery and Suspense 2023, edited by Steph Cha and Lisa Unger (Mariner Books, 2023) reviewed here

87. Amélie Nothomb - First Blood (translated from the French by Alison Anderson, Europa Editions, 2021, 2023) reviewed here

88. Anjum Hasan - A Day in the Life (Penguin 2018) reviewed here

89. Francesca Manfredi - The Empire of Dirt (translated from the Italian by Ekin Oklap, Norton, 2022) reviewed here

90. Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Untamed Shore reviewed here

91. The Haunted Lady by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1942, re-released by American Mystery Classics in 1998) reviewed here

SEPTEMBER

92. Barbara Ehrenreich - Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer (Hachette, 2019) reviewed here

93. Riku Onda - The Aosawa Murders (translated from the Japanese by Alison Watts, Bitter Lemon Press 2020) reviewed here

94. Tara Isabella Burton - Here in Avalon (Simon and Schuster 2024) reviewed here

95. Bae Suah - A Greater Music (Open Letter 2016, translated from the Korean by Deborah K. Smith)

96. The Best American Mystery Stories 2020, edited by C.J. Box (Mariner Books, 2020) reviewed here

97. Kotaro Isaka - The Mantis (Harvill Secker 2023, translated from the Japanese by Sam Malissa) reviewed here

Books in Quarter 4

OCTOBER

98. Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation (Riverhead 2024) reviewed here

99. Anne Michaels - Held (Bloomsbury, 2023) reviewed here

JULY

73. Magdalena Zyzak - The Lady Waiting (Riverhead, 2024) reviewed here

74. Lucy Foley - The Hunting Party (Harper Collins, 2019) reviewed here

75. Lucy Foley - The Midnight Feast (William Morrow, 2024) reviewed here

76. Judith Flanders - Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain (Pan Macmillan, 2024) reviewed here

77. Lee Geum-yi - Can't I Go Instead? (translated from the Korean by An Seonjae, Tor Publishing Group, 2023) reviewed here

78. Danielle Arceneaux - Glory Be (Pegasus 2023) reviewed here

79. Elizabeth Macneal - The Burial Plot (Picador 2024) reviewed here

80. Helen Oyeyemi - Parasol Against the Axe (Riverhead, 2024) reviewed here

81. Shari Lapena - Everyone Here is Lying (Books on Tape, narrated by January LaVoy, 2023)

82. Andrey Kurkov - The Silver Bone (Harper Via, 2024, translated from the Ukrainian by Boris Dralyuk) reviewed here

83. Peter Swanson - A Talent for Murder (Harper Collins, 2024. Audiobook, narrated by several people). reviewed here

84. Sarah Perry - The Essex Serpent (Serpent's Tail, 2016) reviewed here

AUGUST

85. Zhang Yue Ran - Cocoon, translated by Jeremy Tiang (World Editions, 2022) reviewed here

86. The Best American Mystery and Suspense 2023, edited by Steph Cha and Lisa Unger (Mariner Books, 2023) reviewed here

87. Amélie Nothomb - First Blood (translated from the French by Alison Anderson, Europa Editions, 2021, 2023) reviewed here

88. Anjum Hasan - A Day in the Life (Penguin 2018) reviewed here

89. Francesca Manfredi - The Empire of Dirt (translated from the Italian by Ekin Oklap, Norton, 2022) reviewed here

90. Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Untamed Shore reviewed here

91. The Haunted Lady by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1942, re-released by American Mystery Classics in 1998) reviewed here

SEPTEMBER

92. Barbara Ehrenreich - Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer (Hachette, 2019) reviewed here

93. Riku Onda - The Aosawa Murders (translated from the Japanese by Alison Watts, Bitter Lemon Press 2020) reviewed here

94. Tara Isabella Burton - Here in Avalon (Simon and Schuster 2024) reviewed here

95. Bae Suah - A Greater Music (Open Letter 2016, translated from the Korean by Deborah K. Smith)

96. The Best American Mystery Stories 2020, edited by C.J. Box (Mariner Books, 2020) reviewed here

97. Kotaro Isaka - The Mantis (Harvill Secker 2023, translated from the Japanese by Sam Malissa) reviewed here

Books in Quarter 4

OCTOBER

98. Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation (Riverhead 2024) reviewed here

99. Anne Michaels - Held (Bloomsbury, 2023) reviewed here

5rv1988

JULY

This is what I have coming up on my reading list (a text list is below):

Sarah Perry - The Essex Serpent

Andrey Kurkov - The Silver Bone

Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Untamed Shore

Helen Oyeyemi - Parasol Against the Axe

Jo Walton - Tooth and Claw

Writers as Readers: A Celebration of Virago Modern Classics

Ovidia Yu - The Mouse Marathon

Barbara Ehrenreich - Natural Causes: Life, Death, and the Illusion of Control

The O'Henry Prize Stories 2019 - edited by Laura Furman

Vanessa Chan - The Storm We Made

Tan Twan Eng - The House of Doors

Anil Pratinav - Another India: The Making of the World's Largest Muslim Minority, 1947-77

Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai - Dust Child

Jing Tsu - Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern

This is what I have coming up on my reading list (a text list is below):

Sarah Perry - The Essex Serpent

Andrey Kurkov - The Silver Bone

Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Untamed Shore

Helen Oyeyemi - Parasol Against the Axe

Jo Walton - Tooth and Claw

Writers as Readers: A Celebration of Virago Modern Classics

Ovidia Yu - The Mouse Marathon

Barbara Ehrenreich - Natural Causes: Life, Death, and the Illusion of Control

The O'Henry Prize Stories 2019 - edited by Laura Furman

Vanessa Chan - The Storm We Made

Tan Twan Eng - The House of Doors

Anil Pratinav - Another India: The Making of the World's Largest Muslim Minority, 1947-77

Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai - Dust Child

Jing Tsu - Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern

6rv1988

73. Magdalena Zyzak - The Lady Waiting (Riverhead 2024)

Earlier this year, I read The Ballad of Barnabas Pierkiel, a charming, vulgar picaresque fable by Magdalena Zyzak, a Polish filmmaker. It was her debut novel, and I thoroughly enjoyed the wry, dark humour. I was looking forward to her sophomore book, The Lady Waiting, but it doesn't live up to the high standard set by its predecessor. It is a novel about relationships, exploitation, and art theft, and I can see that she's trying for a sort of arch, bleak humour, but doesn't quite succeed. The tone is far too sordid for that, and the end grinds against the rest of the novel like a bone out of joint.

The Lady Waiting is the title of a missing Vermeer, allegedly stolen from a museum, and now making its way around private hands. A substantial reward has been offered for its return. This sets up the premise for our characters. Wioletta, a 21 year old Polish woman, wins the green card lottery but is struggling to thrive in the U.S., her poor English and different upbringing it near impossible to get a job. At an interview, early in the novel, she's asked about her worst qualities, and says she's "manipulating" - the interviewer corrects her, telling her it should be "manipulative"* but does not offer her the job. The interviewer kindly tells her, "We don't admit to such things so much here....that's not really a weakness. As long as you don't talk about it." This is broadly the theme of the novel that follows. Wioletta happens to give a lift to a woman along the highway: flightly, beautiful, capricious Roberta "Bobby" Sleeper, who invites Wioletta to be her assistant/dogsbody. Wioletta rebrands herself as 'Viva', takes on the job, covets her boss' beautiful belongings and his husband, and gets inveigled into a plot to redeem the stolen Vermeer for a small cut of the profits. At some level, she recognises she's being manipulated by Bobby, for whom she becomes "her help, her thief, her lover, her lover's lover." There's a cast of strange hangers-on, including Bobby's various ex-husbands, the wild and angry Polish boy, the smooth and dangerous Russian FSB agent. Yet, Wioletta/Viva was being truthful to that initial interviewer and as you go along, it's not quite clear who is manipulating whom.

While the book itself is fast-paced and moves along rapidly, spanning LA, Italy, Poland, and so on, it's difficult to see this as anything but an inferior take on The Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith. Many of the themes are similar, but Highsmith's execution is subtle, sharp, menacing, while Zyzak leans into lewd, glib, and arch. I prefer the former.

*Edited to correct a typo

Earlier this year, I read The Ballad of Barnabas Pierkiel, a charming, vulgar picaresque fable by Magdalena Zyzak, a Polish filmmaker. It was her debut novel, and I thoroughly enjoyed the wry, dark humour. I was looking forward to her sophomore book, The Lady Waiting, but it doesn't live up to the high standard set by its predecessor. It is a novel about relationships, exploitation, and art theft, and I can see that she's trying for a sort of arch, bleak humour, but doesn't quite succeed. The tone is far too sordid for that, and the end grinds against the rest of the novel like a bone out of joint.

The Lady Waiting is the title of a missing Vermeer, allegedly stolen from a museum, and now making its way around private hands. A substantial reward has been offered for its return. This sets up the premise for our characters. Wioletta, a 21 year old Polish woman, wins the green card lottery but is struggling to thrive in the U.S., her poor English and different upbringing it near impossible to get a job. At an interview, early in the novel, she's asked about her worst qualities, and says she's "manipulating" - the interviewer corrects her, telling her it should be "manipulative"* but does not offer her the job. The interviewer kindly tells her, "We don't admit to such things so much here....that's not really a weakness. As long as you don't talk about it." This is broadly the theme of the novel that follows. Wioletta happens to give a lift to a woman along the highway: flightly, beautiful, capricious Roberta "Bobby" Sleeper, who invites Wioletta to be her assistant/dogsbody. Wioletta rebrands herself as 'Viva', takes on the job, covets her boss' beautiful belongings and his husband, and gets inveigled into a plot to redeem the stolen Vermeer for a small cut of the profits. At some level, she recognises she's being manipulated by Bobby, for whom she becomes "her help, her thief, her lover, her lover's lover." There's a cast of strange hangers-on, including Bobby's various ex-husbands, the wild and angry Polish boy, the smooth and dangerous Russian FSB agent. Yet, Wioletta/Viva was being truthful to that initial interviewer and as you go along, it's not quite clear who is manipulating whom.

While the book itself is fast-paced and moves along rapidly, spanning LA, Italy, Poland, and so on, it's difficult to see this as anything but an inferior take on The Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith. Many of the themes are similar, but Highsmith's execution is subtle, sharp, menacing, while Zyzak leans into lewd, glib, and arch. I prefer the former.

*Edited to correct a typo

7labfs39

>5 rv1988: I quite liked Dust Child, almost as much as The Mountains Sing. Have you read TMS? I'll look forward to your impressions.

8rv1988

As English is actually the third language I learned, I am now questioning whether the title of this thread is correct. "Continues to be"?

9KeithChaffee

>8 rv1988: "Continues to be" is proper and correct English.

10chlorine

>8 rv1988: >9 KeithChaffee: FWIW French words in English is one of my pet peeves (if you want to use French words, speak French! ;) so I preferred your former title. ;)

In class we would not be taught most of the French-origin words (for instance we learned "begin" but not "commence") so I felt cheated when I discovered so many of them were in use: why did we have to learn new words when many of the ones we already knew worked perfectly fine?

In class we would not be taught most of the French-origin words (for instance we learned "begin" but not "commence") so I felt cheated when I discovered so many of them were in use: why did we have to learn new words when many of the ones we already knew worked perfectly fine?

11kjuliff

>10 chlorine: The reason you need to learn old-English derived words as well as French ones is that often there is a subtle difference in meaning. Commence is more formal than begin or start. There is also a difference in pronunciation of what you call French words when used in English. English-French words, like French-French words are both come from Latin. So we’ll get similar words in French, English, Italian and Latin.

After the Norman invasion, French continued to be used by the conquering/upper classes. So the word pig was used for the animal because the farmers used the English word. Whereas the upper class English ate pork from the French porc. Similarly with cow and beef (boeuf). And sometimes it’s just that over time the Latin words have taken on different pronunciations over time.

What you are calling “French words” in English are French derived. English-speakers don’t think they are using a French word when they say “commence”. If fact, they do not pronounce “commence” the way the French do.

Sometimes words are used where there is no equivalent in the native language. Such as “je ne sais quoi” and weekend.

After the Norman invasion, French continued to be used by the conquering/upper classes. So the word pig was used for the animal because the farmers used the English word. Whereas the upper class English ate pork from the French porc. Similarly with cow and beef (boeuf). And sometimes it’s just that over time the Latin words have taken on different pronunciations over time.

What you are calling “French words” in English are French derived. English-speakers don’t think they are using a French word when they say “commence”. If fact, they do not pronounce “commence” the way the French do.

Sometimes words are used where there is no equivalent in the native language. Such as “je ne sais quoi” and weekend.

12kjuliff

>8 rv1988: Either still or continues is correct in the context of your topic titles.

“Still” means being constant, not moving or staying in place (physically or in the point of a topic)

“Continue” means to carry on, moving forward or not stopping.

“The some people were still because they were too shocked at the explosion. Others continued to run in every direction.”.

— edited to fix typos

“Still” means being constant, not moving or staying in place (physically or in the point of a topic)

“Continue” means to carry on, moving forward or not stopping.

“The some people were still because they were too shocked at the explosion. Others continued to run in every direction.”.

— edited to fix typos

13RidgewayGirl

>11 kjuliff: Ha! I was in a French immersion program in school and I didn't even know that the French just called it "le weekend," as I went around calling it "le fin de semaine." Likewise, "le chewing gum" vs. "le gomme a mâcher."

14chlorine

>11 kjuliff: I wasn't entirely serious in my comment about French words. :) You're right that they're French derived.

15rv1988

Thanks all for the comments. I don't entirely trust my 'ear' on the subject of English grammar!

16rv1988

74. and 75. Lucy Foley - The Hunting Party (Harper Collins 2019) and The Midnight Feast (William Morrow, 2024)

I don't think I've read any of Lucy Foley's books before, but she was recommended to me by a member of the (now defunct) mystery novel book club that I was a part of, so I decided to give her a try. I listened to two of her books on my walks home over the last few weeks. They tend to share common themes: rich entitled people committing crimes and getting away with them with poorer exploited friends nursing grudges and taking long delayed revenge years later. Both the The Hunting Party and The Midnight Feast follow this outline. She does tend to write books with multiple points of view, and changing timelines, flipping back and forth between the past and present. Characters will change names over time as well. All of this, plus the plot, should theoretically make this a good mystery, but it isn't handled well at all. As a result, the actual mystery is so clearly telegraphed that it really is not a surprise; there's no twist. The books in themselves pretty forgettable. They worked well for my commute, because I didn't have to give them my full attention.

I don't think I've read any of Lucy Foley's books before, but she was recommended to me by a member of the (now defunct) mystery novel book club that I was a part of, so I decided to give her a try. I listened to two of her books on my walks home over the last few weeks. They tend to share common themes: rich entitled people committing crimes and getting away with them with poorer exploited friends nursing grudges and taking long delayed revenge years later. Both the The Hunting Party and The Midnight Feast follow this outline. She does tend to write books with multiple points of view, and changing timelines, flipping back and forth between the past and present. Characters will change names over time as well. All of this, plus the plot, should theoretically make this a good mystery, but it isn't handled well at all. As a result, the actual mystery is so clearly telegraphed that it really is not a surprise; there's no twist. The books in themselves pretty forgettable. They worked well for my commute, because I didn't have to give them my full attention.

17rv1988

>7 labfs39: I haven't read anything by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai before. I'll look up The Mountains Sing, thank you!

18rv1988

76. Judith Flanders - Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain (Pan Macmillan, 2024)

I actually began reading this last month, but have slowly worked my way to the end this week, after seeing this review in the Times Literary Supplement. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/history/modern-history/rites-of-passage-judith-flander...

It's a fabulous book, rich with detail about mourning customs, practices, and beliefs, and ranges over primary sources, literature and poetry, biographical details of the famous and the poor. Although the research is clearly rigorous, she has a great narrative style, which keeps it eminently readable. The book is organised into chapters that trace death from the first signs (the nursing of the ill) to the final (Victorian beliefs about the afterlife and mourning). In between, are chapters on funeral practices (in which you learn that placing cut flowers on graves is actually a comparatively new practice), on mourning clothes (I learned a lot about how to look after black crepe, the mourning material of choice), on the use of churchyards as spaces for mourning (and play, and gardens), and the gradual transformation of funerals in public and private from religious rites to commercialized practices. Despite the grim subject matter, there is a great deal of tenderness for the unloved and disrespected (as demonstrated by her careful attention to paupers' funerals, as well as the disparity in how suicides by the poor were criminalized and treated as blasphemous, as opposed to the rich, whose suicides were romanticised and forgiven). Unexpectedly, there's also humour: Flanders notes that the social practice of funeral customs had become so widely commercialized and complex that even Victorian cartoonists mocked them (she included pictures of said cartoons). She doesn't waste a lot of time on the more well-documented Victorian matters in this regard; for example, her discussion on grave-robbing for supplies to surgeons is limited, and focuses mostly on the question of *the ethics of allowing surgeons to utilise the bodies of the poor for dissection, against the religious norms and scruples that prevented them from doing so to the rich.

There are so many small and minute details that I found fascinating. Flanders notes, for instance, that early records of deaths were maintained chiefly by women known as ‘searchers,’ who rarely received acknowledgment or credit for the vital data that they collected (chapter 4, ‘Before the Funeral’). Her investigation of Victorian literature also shows the differing attitudes to women remarrying, versus men, and the harsh criticism women received for the way they mourned (she has a great bit from Anthony Trollope, who criticises a woman for mourning too much, yet not enough; for wearing too much black but not appropriately black clothing; for not crying enough except when she cries too much; for being too poor when she married her late husband but for being too rich when he dies). I think the great value of this book is not only the careful and thorough research (and the fact that most of it was achieved during Covid lockdowns!) but also the careful and thoughtful scrutiny she keeps on the class and gender aspects that we, as lay readers, might not know of, or appreciate.

*(edited because I left a sentence incomplete)

I actually began reading this last month, but have slowly worked my way to the end this week, after seeing this review in the Times Literary Supplement. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/history/modern-history/rites-of-passage-judith-flander...

It's a fabulous book, rich with detail about mourning customs, practices, and beliefs, and ranges over primary sources, literature and poetry, biographical details of the famous and the poor. Although the research is clearly rigorous, she has a great narrative style, which keeps it eminently readable. The book is organised into chapters that trace death from the first signs (the nursing of the ill) to the final (Victorian beliefs about the afterlife and mourning). In between, are chapters on funeral practices (in which you learn that placing cut flowers on graves is actually a comparatively new practice), on mourning clothes (I learned a lot about how to look after black crepe, the mourning material of choice), on the use of churchyards as spaces for mourning (and play, and gardens), and the gradual transformation of funerals in public and private from religious rites to commercialized practices. Despite the grim subject matter, there is a great deal of tenderness for the unloved and disrespected (as demonstrated by her careful attention to paupers' funerals, as well as the disparity in how suicides by the poor were criminalized and treated as blasphemous, as opposed to the rich, whose suicides were romanticised and forgiven). Unexpectedly, there's also humour: Flanders notes that the social practice of funeral customs had become so widely commercialized and complex that even Victorian cartoonists mocked them (she included pictures of said cartoons). She doesn't waste a lot of time on the more well-documented Victorian matters in this regard; for example, her discussion on grave-robbing for supplies to surgeons is limited, and focuses mostly on the question of *the ethics of allowing surgeons to utilise the bodies of the poor for dissection, against the religious norms and scruples that prevented them from doing so to the rich.

There are so many small and minute details that I found fascinating. Flanders notes, for instance, that early records of deaths were maintained chiefly by women known as ‘searchers,’ who rarely received acknowledgment or credit for the vital data that they collected (chapter 4, ‘Before the Funeral’). Her investigation of Victorian literature also shows the differing attitudes to women remarrying, versus men, and the harsh criticism women received for the way they mourned (she has a great bit from Anthony Trollope, who criticises a woman for mourning too much, yet not enough; for wearing too much black but not appropriately black clothing; for not crying enough except when she cries too much; for being too poor when she married her late husband but for being too rich when he dies). I think the great value of this book is not only the careful and thorough research (and the fact that most of it was achieved during Covid lockdowns!) but also the careful and thoughtful scrutiny she keeps on the class and gender aspects that we, as lay readers, might not know of, or appreciate.

*(edited because I left a sentence incomplete)

19FlorenceArt

>18 rv1988: Sounds very interesting!

ETA: just saw she also wrote The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime.

ETA: just saw she also wrote The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime.

20labfs39

>18 rv1988: That sounds interesting. Not a book I would pick up on my own, but your review may persuade me.

21RidgewayGirl

>16 rv1988: I just finished a terrible legal thriller for my mystery book club and I wonder if it might have gone down easier if I'd listened to it with half and ear while doing other things. Something to keep in mind for next time (I like the people in that book club enormously, but the tendency to want to read from a variety of sub-genres does not always serve us well.)

22rv1988

>19 FlorenceArt: Indeed! The Invention of Murder is on my TBR. I'm quite looking forward to it.

>20 labfs39: It was a bit of a random read for me too, but I ended up liking it.

>21 RidgewayGirl: Ooh, which legal thriller? My mystery book club has sadly died out. I think people have just been busy with life. I'm the only one of my friends who isn't a parent, and so I quite understand!

>20 labfs39: It was a bit of a random read for me too, but I ended up liking it.

>21 RidgewayGirl: Ooh, which legal thriller? My mystery book club has sadly died out. I think people have just been busy with life. I'm the only one of my friends who isn't a parent, and so I quite understand!

23RidgewayGirl

>22 rv1988: It's called The Plinko Bounce by Martin Clark. I am hoping that I will be able to be diplomatic about what I think about it if it turns out that the person who suggested it is a fan of the author (it will change how I think about them, if that is the case.)

24rv1988

>23 RidgewayGirl: Thank you! The NYT called the author "the thinking man's John Grisham" - but it's not the first them they've been wrong.

25rv1988

77. Lee Geum-yi - Can't I Go Instead? (translated from the Korean by An Seonjae, Tor Publishing Group, 2023)

I had this on my list of interesting translations from 2023; the original was published in Korean in 2016.

The subject matter of this book is complex and powerful (the war between Korea and Japan, World War II, Korean independence, the abuse of Korean 'comfort' women by the Japanese army). The story revolves around two women: the daughter of a wealthy Korean nobleman who collaborates with the Japanese when they occupy his country, and the young woman he purchases and enslaves, to be his daughter's companion. It is a little bizarre, and very disconcerting, to have these difficult and distressing themes narrated in the tone and style of a disengaged teenager. I can't tell if it is the way it was translated, or if that's the fault of the original text, but the writing on these subjects was not well done, and seemed almost glib and facile. Additionally, there are so many grammatical and syntactical errors in the English translation, which ought to have been addressed by the publishers. It is particularly unfortunate when you think of the many excellent examples of literature that already exist on similar themes, which demonstrate how skillfully and sensitively they *could* have been handled (e.g. Pachinko). All in all, would not recommend.

I had this on my list of interesting translations from 2023; the original was published in Korean in 2016.

The subject matter of this book is complex and powerful (the war between Korea and Japan, World War II, Korean independence, the abuse of Korean 'comfort' women by the Japanese army). The story revolves around two women: the daughter of a wealthy Korean nobleman who collaborates with the Japanese when they occupy his country, and the young woman he purchases and enslaves, to be his daughter's companion. It is a little bizarre, and very disconcerting, to have these difficult and distressing themes narrated in the tone and style of a disengaged teenager. I can't tell if it is the way it was translated, or if that's the fault of the original text, but the writing on these subjects was not well done, and seemed almost glib and facile. Additionally, there are so many grammatical and syntactical errors in the English translation, which ought to have been addressed by the publishers. It is particularly unfortunate when you think of the many excellent examples of literature that already exist on similar themes, which demonstrate how skillfully and sensitively they *could* have been handled (e.g. Pachinko). All in all, would not recommend.

26labfs39

>25 rv1988: Have you read the graphic work Grass by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim? It's the best book I've read on comfort women. Which books would would you recommend on the occupation of Korea and the accompanying issues? I've read Pachinko and watched the tv series, at least the episodes that have been released so far. I was pleasantly surprised at how good the tv adaptation was.

27rv1988

>26 labfs39: I have! Grass is the other book I was thinking of.

28labfs39

>27 rv1988: I also another graphic work by Gendry-Kim called The Waiting, about people waiting for their number to be drawn for a reunification visit with their family in North Korea. I didn't think it was quite as good, but it was still worth a read.

29RidgewayGirl

>24 rv1988: LOL, no. John Grisham is a far better writer. The worldview was so simplistic and fundamentally callous. I am very curious about our book club meeting on Thursday.

30rv1988

>28 labfs39: Oh, this sounds interesting. Thank you for the recommendation. I've added it to my list.

>29 RidgewayGirl: I hope the discussion is entertaining! My dormant mystery group decided to restart, the book we've chosen is also something I am slightly hate-reading, so I think we're in the same boat.

>29 RidgewayGirl: I hope the discussion is entertaining! My dormant mystery group decided to restart, the book we've chosen is also something I am slightly hate-reading, so I think we're in the same boat.

31rv1988

78. Danielle Arceneaux - Glory Be (Pegasus 2023)

I was in the mood for something light and easy and this did the trick. A short little murder mystery, featuring Glory Broussard, a devout, church-going Black lady, with an absent husband, a successful daughter in New York, and a lot of time on her hands. She manages a small gambling business from a coffee shop table, nurses a grudge against her sister, and in this novel, investigates the murder of her best friend, a nun. Although the death was ruled a suicide, Glory is convinced there's something else going, and pokes into local politics in Lafayette, Louisiana, until she can figure it out. The writing is not great, but the story is well-developed, the characters memorable, and it is pleasant enough. As this is a debut novel, I'm looking forward to more.

I was in the mood for something light and easy and this did the trick. A short little murder mystery, featuring Glory Broussard, a devout, church-going Black lady, with an absent husband, a successful daughter in New York, and a lot of time on her hands. She manages a small gambling business from a coffee shop table, nurses a grudge against her sister, and in this novel, investigates the murder of her best friend, a nun. Although the death was ruled a suicide, Glory is convinced there's something else going, and pokes into local politics in Lafayette, Louisiana, until she can figure it out. The writing is not great, but the story is well-developed, the characters memorable, and it is pleasant enough. As this is a debut novel, I'm looking forward to more.

32rv1988

The shortlist for the Singapore Literature Prize was announced, in Tamil, Chinese, Malay and English. As English is the only one of these languages I can read (I can speak a little Tamil, but I can't read it at all), here are the shortlisted books. I'm going to try and read as many as I can!

https://www.bookcouncil.sg/slp-2024

Fiction:

Myle Yan Tay - Catskull

Suchene Christine Lim - Dearest Intimate

Prasanthi Ram - Nine Yard Sarees (I don't have the book but I do have a nine yard saree)

Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation (I have a copy of this one)

Nisha Mehraj - We Do Not Make Love Here

Nonfiction:

Peter Ellinger - Down Memory Lane: Peter Ellinger's Memoirs

Shubhigi Rao - Pulp III: An Intimate Inventory of the Banished Book

Jee Leong Koh - Sample and Loop: A Simple History of Singaporeans in America

Chan Lee Shan - Searching for Lee Wen

Dana Lam - The Art of Being a Grandmother: An Incomplete Diary of Becoming

Translated:

Acharya Chatursen - Bride of the City (translated from the Hindi by Pratibha Vinod Kumar and A.K.Kulshreshth)

Zhang Yueran - Cocoon (translated from the Chinese by Jeremy Tiang)

Shuang Xuetao - Rouge Street: Three Novellas (translated from the Chinese by Jeremy Tiang)

Liang Wern Fook - The Joy of a Left Hand (translated from the Chinese by Christina Ng)

https://www.bookcouncil.sg/slp-2024

Fiction:

Myle Yan Tay - Catskull

Suchene Christine Lim - Dearest Intimate

Prasanthi Ram - Nine Yard Sarees (I don't have the book but I do have a nine yard saree)

Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation (I have a copy of this one)

Nisha Mehraj - We Do Not Make Love Here

Nonfiction:

Peter Ellinger - Down Memory Lane: Peter Ellinger's Memoirs

Shubhigi Rao - Pulp III: An Intimate Inventory of the Banished Book

Jee Leong Koh - Sample and Loop: A Simple History of Singaporeans in America

Chan Lee Shan - Searching for Lee Wen

Dana Lam - The Art of Being a Grandmother: An Incomplete Diary of Becoming

Translated:

Acharya Chatursen - Bride of the City (translated from the Hindi by Pratibha Vinod Kumar and A.K.Kulshreshth)

Zhang Yueran - Cocoon (translated from the Chinese by Jeremy Tiang)

Shuang Xuetao - Rouge Street: Three Novellas (translated from the Chinese by Jeremy Tiang)

Liang Wern Fook - The Joy of a Left Hand (translated from the Chinese by Christina Ng)

33RidgewayGirl

>32 rv1988: That's a great list (I only looked at the fiction). I enjoyed Rouge Street when I read it and I've added Cocoon and The Great Reclamation to my wishlist. As usual, several of the books are not (yet) available in the US.

34labfs39

>32 rv1988: Interesting that two of the four translations are by Jeremy Tiang.

35rv1988

>33 RidgewayGirl: I'm looking forward to The Great Reclamation too.

>34 labfs39: Yes, I've read one of his books but I didn't know he translated as well.

>34 labfs39: Yes, I've read one of his books but I didn't know he translated as well.

36rv1988

79. Elizabeth Macneal - The Burial Plot (Picador 2024)

Another 'walking' read. The Burial Plot is set in London, 1839. Bonnie runs away from home to avoid being forced to wed the vicar; although he paid for her to be educated, she wants to choose her own life and own fate. She meets Crawford, a manipulative, cruel, but charismatic con man who romances and rejects Bonnie with equal measure. With Crawford's friend Rex, they run cons, until one day, Bonnie kills a man in self-defence. To keep her out of London and away from suspicion, Crawford fakes her a recommendation letter, and gets her a place as a lady's maid in Endellion House, a massive, crumbling neo-Victorian mansion. Endellion is owned by Mr Moncrieff, an eccentric architect and widower who sits in office, obsessively drawing up designs for a mausoleum for his dead wife. Bonnie works for his daughter Cissie, a strange, quiet teenager who writes love-letters to herself from a mysterious lord, when she's not reading romance novels. At first, things are going well - Bonnie settles in, the Moncrieffs treat her well, and the work suits her. She suggests that Mr Moncrieff convert part of his lands into a cemetery, and to her surprise, he actually takes her suggestion seriously, and credits her for it. She has the run of the gardens, and loves plants, and seeing this, Mr Moncrieff lets her help design the proposed cemetery gardens. Even though there are rumours swirling around the village about how Mrs Moncrieff died, Bonnie finds a home in Endellion. But then Crawford shows up, full of plans to con the Moncrieffs out of the house, pretending to be Bonnie's brother while sneaking into her room at night. Bonnie is drawn into his plans again, and this time, no one might survive them.

. I will say the plot is nothing special, and should also warn that there's a lot of violence, and sexual violence, including mentions of such violence against a child (which I fast-forwarded through, to be honest). Still, this was a very well-written novel, and I enjoyed listening to it, with the story gripping enough to keep me going and even speed up my pace a bit during the tenser moments. It was especially interesting because I just read Judith Flanders - Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain and a lot of the discussion around the funeral rites, the graveyard design, and mourning made more sense. It's a well-researched, tightly written story, and I do plan on reading more by the author.

Another 'walking' read. The Burial Plot is set in London, 1839. Bonnie runs away from home to avoid being forced to wed the vicar; although he paid for her to be educated, she wants to choose her own life and own fate. She meets Crawford, a manipulative, cruel, but charismatic con man who romances and rejects Bonnie with equal measure. With Crawford's friend Rex, they run cons, until one day, Bonnie kills a man in self-defence. To keep her out of London and away from suspicion, Crawford fakes her a recommendation letter, and gets her a place as a lady's maid in Endellion House, a massive, crumbling neo-Victorian mansion. Endellion is owned by Mr Moncrieff, an eccentric architect and widower who sits in office, obsessively drawing up designs for a mausoleum for his dead wife. Bonnie works for his daughter Cissie, a strange, quiet teenager who writes love-letters to herself from a mysterious lord, when she's not reading romance novels. At first, things are going well - Bonnie settles in, the Moncrieffs treat her well, and the work suits her. She suggests that Mr Moncrieff convert part of his lands into a cemetery, and to her surprise, he actually takes her suggestion seriously, and credits her for it. She has the run of the gardens, and loves plants, and seeing this, Mr Moncrieff lets her help design the proposed cemetery gardens. Even though there are rumours swirling around the village about how Mrs Moncrieff died, Bonnie finds a home in Endellion. But then Crawford shows up, full of plans to con the Moncrieffs out of the house, pretending to be Bonnie's brother while sneaking into her room at night. Bonnie is drawn into his plans again, and this time, no one might survive them.

. I will say the plot is nothing special, and should also warn that there's a lot of violence, and sexual violence, including mentions of such violence against a child (which I fast-forwarded through, to be honest). Still, this was a very well-written novel, and I enjoyed listening to it, with the story gripping enough to keep me going and even speed up my pace a bit during the tenser moments. It was especially interesting because I just read Judith Flanders - Rites of Passage: Death & Mourning in Victorian Britain and a lot of the discussion around the funeral rites, the graveyard design, and mourning made more sense. It's a well-researched, tightly written story, and I do plan on reading more by the author.

37rv1988

80. Helen Oyeyemi - Parasol Against the Axe (Riverhead, 2024)

I really struggled with this one - partly, because I think I was not in the right frame of mind for it, and partly because the style is almost deliberately inaccessible. Sentences run into each other, the dialogues are deeply stylized and layered, and nothing is quite what it seems, with metaphor piled on metaphor and misdirection rife. Oyeyemi has lived in Prague for several years now, and this seems to be her tribute to the city: a novel that envisions it as a living, wilful, conniving creature. Parasol Against the Axe has a plot of sorts but it doesn't matter: the book is not about the plot, or the characters, but about Prague.

In Parasol Against The Axe, Hero Tojosoa goes to Prague for the wedding of her friend Sofie, and brings along a book that her son gifted her, titled Paradoxical Undressing , written allegedly by a Sydney bartender named Merlin Mwenda. While the preparations for the wedding seems to be going well, someone spots Dorothea Gilmartin, a former friend of Sofie and Hero's, with whom they had a falling out. Oyeyemi tells us, "...Now, if Hero Tojosoa was an axe, then Dorothea Gilmartin was a parasol. Really both were both, of course, but you try telling them that." Oyeyemi does not elaborate further. We know that Hero is a journalist of sorts, and Dorothea, an heiress who performs mysterious unspecified tasks for clients. We learn also, that Dorothea is looking for Hero, as much as Hero is dodging her. In chapters alternating between their cat and mouse chase over Prague (worst bachelorette ever, by the way), each of them is reading their own copy of Paradoxical Undressing . The excerpts from this book within the book show us that Paradoxical Undressing changes not only depending on who is reading it, but each time someone reads it. Intervening in their lives, and the narrative, is Prague itself, appearing through various figures: a hair dresser, a woman dressed as a mole, and so on.

This book is confounding, with each layer of sense undone promptly in the next sentence. Dorothea Gilmartin is not even a real name: it's Hero's nom de plume, that not-Dorothea adopted after reading a book that Hero wrote. When asked what she thought about the book, not-Dorothea says, "Think? I couldn't. It walked all over me and wiped its feet on my hair." Parasol Against the Axe was ruder than that.

(edited for grammar)

I really struggled with this one - partly, because I think I was not in the right frame of mind for it, and partly because the style is almost deliberately inaccessible. Sentences run into each other, the dialogues are deeply stylized and layered, and nothing is quite what it seems, with metaphor piled on metaphor and misdirection rife. Oyeyemi has lived in Prague for several years now, and this seems to be her tribute to the city: a novel that envisions it as a living, wilful, conniving creature. Parasol Against the Axe has a plot of sorts but it doesn't matter: the book is not about the plot, or the characters, but about Prague.

In Parasol Against The Axe, Hero Tojosoa goes to Prague for the wedding of her friend Sofie, and brings along a book that her son gifted her, titled Paradoxical Undressing , written allegedly by a Sydney bartender named Merlin Mwenda. While the preparations for the wedding seems to be going well, someone spots Dorothea Gilmartin, a former friend of Sofie and Hero's, with whom they had a falling out. Oyeyemi tells us, "...Now, if Hero Tojosoa was an axe, then Dorothea Gilmartin was a parasol. Really both were both, of course, but you try telling them that." Oyeyemi does not elaborate further. We know that Hero is a journalist of sorts, and Dorothea, an heiress who performs mysterious unspecified tasks for clients. We learn also, that Dorothea is looking for Hero, as much as Hero is dodging her. In chapters alternating between their cat and mouse chase over Prague (worst bachelorette ever, by the way), each of them is reading their own copy of Paradoxical Undressing . The excerpts from this book within the book show us that Paradoxical Undressing changes not only depending on who is reading it, but each time someone reads it. Intervening in their lives, and the narrative, is Prague itself, appearing through various figures: a hair dresser, a woman dressed as a mole, and so on.

This book is confounding, with each layer of sense undone promptly in the next sentence. Dorothea Gilmartin is not even a real name: it's Hero's nom de plume, that not-Dorothea adopted after reading a book that Hero wrote. When asked what she thought about the book, not-Dorothea says, "Think? I couldn't. It walked all over me and wiped its feet on my hair." Parasol Against the Axe was ruder than that.

(edited for grammar)

38FlorenceArt

>37 rv1988: Sounds weirdly intriguing!

39labfs39

>38 FlorenceArt: I agree, Florence. >37 rv1988: You many not have liked it, Rasdhar, but you write a fascinating review.

40rv1988

>38 FlorenceArt: >39 labfs39: To be honest, I'm not sure what I feel about it. I think I liked it, but also I found it challenging.

41RidgewayGirl

>37 rv1988: I've read two books by Oyeyemi, Peaces and What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours and I liked her short stories, but found the novel inscrutable. It felt like things were happening so randomly that I had no way to grasp any of it.

42rv1988

>41 RidgewayGirl: I read and liked her book, Mr Fox, which is more accessible, I feel. Everything she wrote after that has been progressively more obscure and difficult to read. I think she's writing for a small pool of MFA candidates, and I'm not in that pool.

43rv1988

81. Shari Lapena - Everyone Here is Lying (Books on Tape, narrated by January LaVoy, 2023)

I've been on my feet for the last couple of days and ended up listening to a lot of books, including this one. I picked light thrillers on purpose, because they provide just the right amount of mindless content that doesn't require me to fully engage but still have the surface level distraction to get through menial work. This is not a good novel, but it didn't have to be for me, and that's fine. I'm just not sure why it received such glowing reviews across the board last year, given how mediocre it was.

I've been on my feet for the last couple of days and ended up listening to a lot of books, including this one. I picked light thrillers on purpose, because they provide just the right amount of mindless content that doesn't require me to fully engage but still have the surface level distraction to get through menial work. This is not a good novel, but it didn't have to be for me, and that's fine. I'm just not sure why it received such glowing reviews across the board last year, given how mediocre it was.

44rv1988

82. Andrey Kurkov - The Silver Bone (Harper Via, 2024, translated from the Ukrainian by Boris Dralyuk)

In Kyiv, 1919, Samson Kolechko is walking home with his father, when Cossacks attack. His father is dead, and Samson's ear is severed. With no other family, and many factions fighting for control of Ukraine, Samson has no option but to find a way to support himself. He writes out a statement for the police, and noting the clarity of his writing and thoughts, they hire him. With only a marksmanship course under his belt, he proceeds to investigate crime, even as rebellions, violence, and war continue to unfold around him. As he works, he finds that he has an unusual ability: his severed ear, which he stored in a candy tin, neither decays nor disconnects from him - instead, he can hear whatever is being said in its vicinity.

This book is not precisely a mystery novel, in that it isn't deeply plotted, or contains an unexpected twist. Instead, it just unfolds atmospherically, containing hundreds of tiny, little details that give you an uncomfortable look into what it is like to live with occupation, conflict, and war. Samson's investigation occurs even as the electricity runs out, for lack of fuel or workers, with scarce food and no salt, with lice and rats infesting the living environment. There's a sense of unreality to it: on one day, a fellow policeman is killed while quelling a rebellion, on the next day, he sits and records statements about a theft of bread from a bakery.

I did enjoy it, but I don't think it was Booker material. The Booker reading guide is very useful, though, with lots of information from the author, translators, and so on. https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/reading-guide-the-silver...

In Kyiv, 1919, Samson Kolechko is walking home with his father, when Cossacks attack. His father is dead, and Samson's ear is severed. With no other family, and many factions fighting for control of Ukraine, Samson has no option but to find a way to support himself. He writes out a statement for the police, and noting the clarity of his writing and thoughts, they hire him. With only a marksmanship course under his belt, he proceeds to investigate crime, even as rebellions, violence, and war continue to unfold around him. As he works, he finds that he has an unusual ability: his severed ear, which he stored in a candy tin, neither decays nor disconnects from him - instead, he can hear whatever is being said in its vicinity.

This book is not precisely a mystery novel, in that it isn't deeply plotted, or contains an unexpected twist. Instead, it just unfolds atmospherically, containing hundreds of tiny, little details that give you an uncomfortable look into what it is like to live with occupation, conflict, and war. Samson's investigation occurs even as the electricity runs out, for lack of fuel or workers, with scarce food and no salt, with lice and rats infesting the living environment. There's a sense of unreality to it: on one day, a fellow policeman is killed while quelling a rebellion, on the next day, he sits and records statements about a theft of bread from a bakery.

I did enjoy it, but I don't think it was Booker material. The Booker reading guide is very useful, though, with lots of information from the author, translators, and so on. https://thebookerprizes.com/the-booker-library/features/reading-guide-the-silver...

45labfs39

>44 rv1988: Thanks for this review and for alerting me to the Booker reading guides. I was not aware of them. I read the one for This Other Eden and wish I had read it before our book club discussion of the book.

46RidgewayGirl

>43 rv1988: Light thrillers are what works for me on audio, too. Anything more substantial and I feel like I'm shortchanging the book as I'm a better reader with my eyes than my ears. I've also started listening to short stories which also seem to work for me.

47rv1988

>45 labfs39: Aren't they great? I should use them more.

>46 RidgewayGirl: I think you've mentioned short stories in this context before: I will try that next, as all the thrillers I've read recently have been disappointing.

>46 RidgewayGirl: I think you've mentioned short stories in this context before: I will try that next, as all the thrillers I've read recently have been disappointing.

48rv1988

83. Peter Swanson - A Talent for Murder (Harper Collins, 2024. Audiobook, narrated by several people).

This was terrible. Swanson has an ongoing series about a woman named Lily Kintner, who is some variety of -path (psycho, socio, osteo, I'm not sure). This is the third book in the series. We already know from books 1 and 2 that she'skilled several people and gotten away with it and is currently unemployed and living at home with her divorced, yet unhappily co-habiting parents, while conducting a handwritten letter-based flirtation with the cop who once investigated her. In this novel, Lily is contacted by a old college friend, Martha. Martha has noticed an odd pattern of deaths that occurred in the cities where her husband, a travelling salesman, has been, of late. She contacts Lily because in grad school, Martha was in a relationship with a terrifying man who hurt her, and Lily helped her end it. So Martha and Lily decided to investigate and see if Martha's right, and whether she should in fact go to the police about her husband. The initial premise is stupid enough, but then the plot gets progressively stupider and more unbelievable, and not in a fun way. Why do I keep reading these books? Masochism, probably.

This was terrible. Swanson has an ongoing series about a woman named Lily Kintner, who is some variety of -path (psycho, socio, osteo, I'm not sure). This is the third book in the series. We already know from books 1 and 2 that she's

49rv1988

84. Sarah Perry - The Essex Serpent (Serpent's Tail, 2016)

This was such an excellent read. I feel relieved and glad that after all these terrible thrillers, I finally had the chance to really enjoy some excellent prose. Perry has such a beautiful turn of phrase, and such a remarkable, elegant ability to characterise people. You can know all of them in just a few sentences.

The Essex Serpent is set during the course of one year in the 1890s, in England. At New Years, Cora Seaborne's unpleasant, abusive husband dies. Relieved and grateful, she relocates from London to Essex with her companion, Martha, a staunch socialist, and her son Francis. Although it isn't explicitly stated, Francis is on the spectrum. Cora herself, fascinated by the natural world, collects fossils and reads politics; she wears men's boots and walks among the woods and does not conduct herself like a Victorian widow. In Essex, she is introduced to the local reverend, William Ransome: theirs is an immediate meeting of minds, but also, an impossible one. William is married to his beloved, beautiful Stella, whom he adores, and Cora has eschewn every last trace of her womanhood, largely because of her awful marriage. In Essex, they are both caught up with local legends of a massive serpent that is said to be lurking the waters around. This is at a time when paleontology, natural sciences, and so on are in fashion, and Cora wonders if a recent earthquake in the region has not revealed some prehistoric relic. At the other end, William tries to keep his congregation in check, as they increasingly see in the serpent the signs of evil and death: every last misfortune, from curdled milk to missing animals, is blamed on the Essex serpent. By the end of the year all secrets are revealed, and each character, from Cora and William, to the most minute figure to appear on the pages (a local begger, the fisherman's daughter, the fisherman himself, who has lost his boat, the surgeon and his friend, the patient that Martha befriends) have each renegotiated, with themselves, the conditions under which they can live, and chosen their own path, or come to terms with the paths available to them.

This novel is so rich in detail and texture. There are dozens of ideas, concepts, themes, and characters, but it feels dense and diverse and not crowded, as it might have done in the hands of a less skilful writer. It isn't just about the evolution of science, or how Darwin's work transformed Victorian faith, or about the development of surgical techniques, or the changes in laws for the housing of the poor and indigent, but about all of these things, and then also, about love, romance, friendship, adoration. I loved, more than anything, how she could tell you all about each character so deftly, in spare, but vivid prose. Cora's friend and admirer, Luke Garrett is "thirty-two: a surgeon with a hungry disobedient mind," the Reverend William's faith is "felt deeply, and above all, out of doors, where the vaulted sky was his cathedral and the oaks its transept pillars," Maureen Fry, a nurse who longed to be a surgeon but could not, as as a woman, wields "an implacable serenity...as a weapon against the arrogance of men...". You can see right to their core from her sparse description, but when it comes to the world that Cora and William see, one through the sharp eyes of scientific rigour, the other through the ardour of fate, her language turns lush and descriptive. If she wrote about a trip to the grocery store, I'd probably be fascinated.

I think this nice review in the Guardian does a far better job than I could, so I am linking it below, but how nice it was to have writing that I could truly savour, and not get through to find out what happened at the end.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/jun/16/the-essex-serpent-sarah-perry-revi...

This was such an excellent read. I feel relieved and glad that after all these terrible thrillers, I finally had the chance to really enjoy some excellent prose. Perry has such a beautiful turn of phrase, and such a remarkable, elegant ability to characterise people. You can know all of them in just a few sentences.

The Essex Serpent is set during the course of one year in the 1890s, in England. At New Years, Cora Seaborne's unpleasant, abusive husband dies. Relieved and grateful, she relocates from London to Essex with her companion, Martha, a staunch socialist, and her son Francis. Although it isn't explicitly stated, Francis is on the spectrum. Cora herself, fascinated by the natural world, collects fossils and reads politics; she wears men's boots and walks among the woods and does not conduct herself like a Victorian widow. In Essex, she is introduced to the local reverend, William Ransome: theirs is an immediate meeting of minds, but also, an impossible one. William is married to his beloved, beautiful Stella, whom he adores, and Cora has eschewn every last trace of her womanhood, largely because of her awful marriage. In Essex, they are both caught up with local legends of a massive serpent that is said to be lurking the waters around. This is at a time when paleontology, natural sciences, and so on are in fashion, and Cora wonders if a recent earthquake in the region has not revealed some prehistoric relic. At the other end, William tries to keep his congregation in check, as they increasingly see in the serpent the signs of evil and death: every last misfortune, from curdled milk to missing animals, is blamed on the Essex serpent. By the end of the year all secrets are revealed, and each character, from Cora and William, to the most minute figure to appear on the pages (a local begger, the fisherman's daughter, the fisherman himself, who has lost his boat, the surgeon and his friend, the patient that Martha befriends) have each renegotiated, with themselves, the conditions under which they can live, and chosen their own path, or come to terms with the paths available to them.

This novel is so rich in detail and texture. There are dozens of ideas, concepts, themes, and characters, but it feels dense and diverse and not crowded, as it might have done in the hands of a less skilful writer. It isn't just about the evolution of science, or how Darwin's work transformed Victorian faith, or about the development of surgical techniques, or the changes in laws for the housing of the poor and indigent, but about all of these things, and then also, about love, romance, friendship, adoration. I loved, more than anything, how she could tell you all about each character so deftly, in spare, but vivid prose. Cora's friend and admirer, Luke Garrett is "thirty-two: a surgeon with a hungry disobedient mind," the Reverend William's faith is "felt deeply, and above all, out of doors, where the vaulted sky was his cathedral and the oaks its transept pillars," Maureen Fry, a nurse who longed to be a surgeon but could not, as as a woman, wields "an implacable serenity...as a weapon against the arrogance of men...". You can see right to their core from her sparse description, but when it comes to the world that Cora and William see, one through the sharp eyes of scientific rigour, the other through the ardour of fate, her language turns lush and descriptive. If she wrote about a trip to the grocery store, I'd probably be fascinated.

I think this nice review in the Guardian does a far better job than I could, so I am linking it below, but how nice it was to have writing that I could truly savour, and not get through to find out what happened at the end.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/jun/16/the-essex-serpent-sarah-perry-revi...

50labfs39

>49 rv1988: Your review makes me think this is a book I must seek out. Different from my usual fare, but I love well-written characters.

51RidgewayGirl

>48 rv1988: I'm sorry you read that terrible book, but I was very entertained by your review.

>49 rv1988: I really love this book.

>49 rv1988: I really love this book.

52FlorenceArt

>49 rv1988: Thank you for your review. I wishlisted this.

53rv1988

AUGUST

It's a busy month with the semester starting, so I'll update this later! Just placeholding it for now.

Currently reading (carry-overs from last month):

The O'Henry Prize Stories 2019 - edited by Laura Furman

Writers as Readers: A Celebration of Virago Modern Classics

Upcoming:

I know I won't get around to all of these, but here's what is on the bedside table in a tottering mountain:

Silvia Moreno-Garcia - Untamed Shore

Barbara Ehrenreich - Natural Causes: Life, Death, and the Illusion of Control

Vanessa Chan - The Storm We Made

Tan Twan Eng - The House of Doors

Anil Pratinav - Another India: The Making of the World's Largest Muslim Minority, 1947-77

Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai - Dust Child

Jing Tsu - Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern

Christopher Moore - A Dirty Job

Nadine Akkerman - Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth-Century Britain

Alvaro Enrigue - You Dreamed of Empires

Su Pae - A Greater Music

Mary Roberts Rhinehart - The Haunted Lady

Francesca Manfredi - The Empire of Dirt

I had picked up two books in July that I've decided not to take up, for now - perhaps later: Jo Walton - Tooth and Claw and Ovidia Yu - The Mouse Marathon

Currently reading (carry-overs from last month):

The O'Henry Prize Stories 2019 - edited by Laura Furman

Writers as Readers: A Celebration of Virago Modern Classics

Upcoming:

I know I won't get around to all of these, but here's what is on the bedside table in a tottering mountain:

Vanessa Chan - The Storm We Made

Tan Twan Eng - The House of Doors

Anil Pratinav - Another India: The Making of the World's Largest Muslim Minority, 1947-77

Rachel Heng - The Great Reclamation

Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai - Dust Child

Jing Tsu - Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern

Christopher Moore - A Dirty Job

Nadine Akkerman - Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth-Century Britain

Alvaro Enrigue - You Dreamed of Empires

I had picked up two books in July that I've decided not to take up, for now - perhaps later: Jo Walton - Tooth and Claw and Ovidia Yu - The Mouse Marathon

55rv1988

>54 labfs39: Thank you!

57rv1988

And with reference to my >37 rv1988: earlier comments of Helen Oyeyemi's Parasol Against the Axe, here's a better review than I could write. I don't agree with all of it (she likes Oyeyemi far more than I do, and won't concede the pretentiousness) but she does catch what is interesting and confounding about her writing:

Sarah Chihaya, The Ghosts of Prague: Helen Oyeyemi and the borderlands of realism (The Nation)

https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/helen-oyeyemi-parasol-against-axe/

In Parasol Against the Axe, books desire readers and cities desire visitors and residents—a reversal of the anthropocentric way we’re used to thinking about these interactions. It is these reversals that Oyeyemi ultimately seems interested in narrating: What might it look like if books and cities really could speak for themselves, aside from their authors or various kinds of human ambassadors? Or if, instead of a reader’s impression of a book, we were somehow party to the book’s impression of its readers? Likewise, imagine that instead of a travelogue, we could get a sense of the city’s own judgmental log of the travelers who pass through it. While some of Oyeyemi’s earlier books disassembled and reconstructed familiar fairy tales—Mr. Fox took on “Bluebeard,” Boy Snow Bird looked at “Snow White,” and Gingerbread toyed with “Hansel and Gretel”—Parasol Against the Axe is more interested in interrogating the fairy-tale logic we take for granted in real life. Here, the magical belief under examination is the idea that anyone can ever really know a city or a text comprehensively. The “Prague book” is like Prague itself: It has other ideas about what it is that transcend any one reader’s or visitor’s conception. Books and cities, Oyeyemi argues, have lives of their own.

Sarah Chihaya, The Ghosts of Prague: Helen Oyeyemi and the borderlands of realism (The Nation)

https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/helen-oyeyemi-parasol-against-axe/

58rv1988