1thorold

Welcome to my Q4 thread. The previous thread was here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/361815

My Q4 starts off with another trip to visit my subsidiary book-pile (and the OH) in Cleveland. I’ll have to see how much reading I get done this time. There are currently only four unread books on the pile, but I’m sure that will change quickly as I’m led into temptation…

Otherwise, my general reading plans include the last phase of the “world tour”, which most recently landed me in Peru. I’ll probably continue via Chile and Argentina before crossing the Atlantic to head back to my starting point in Belgium. Maybe there will be time to pass through a bit of Africa on the way.

There’s also the Reading Globally “Island nations” theme read — I haven’t quite worked out what I’m going to pick for that yet, but I’m sure inspiration will strike. There’s a Trinidadian on the pile, so that may be the starting point.

And of course I want to carry on with my Canetti project. There are two more volumes of memoirs already on my (Dutch) pile.

My Q4 starts off with another trip to visit my subsidiary book-pile (and the OH) in Cleveland. I’ll have to see how much reading I get done this time. There are currently only four unread books on the pile, but I’m sure that will change quickly as I’m led into temptation…

Otherwise, my general reading plans include the last phase of the “world tour”, which most recently landed me in Peru. I’ll probably continue via Chile and Argentina before crossing the Atlantic to head back to my starting point in Belgium. Maybe there will be time to pass through a bit of Africa on the way.

There’s also the Reading Globally “Island nations” theme read — I haven’t quite worked out what I’m going to pick for that yet, but I’m sure inspiration will strike. There’s a Trinidadian on the pile, so that may be the starting point.

And of course I want to carry on with my Canetti project. There are two more volumes of memoirs already on my (Dutch) pile.

3thorold

I’m in Ohio again, and the first book I finished in Q4 was the one I started on last week’s transatlantic flight, the sixth of seven parts of J J Voskuil’s career-length novel of office life, Het Bureau, part one of which I read in April 2020:

Afgang (2000) by J J Voskuil (NL, 1926-2008)

The penultimate part of Het Bureau takes us into the mid-1980s, when office life had been changed forever by the invention of the Post-It note and the computer was making inroads even into the humanities and social sciences. Government cuts are still the flavour of the moment, and the Institute seems to be under threat.

Maarten Koning is now in his late fifties, starting to become a little battle-weary, and he declines to apply for the post when his boss for the last twenty years, Jaap Balk, steps down. There’s a lot of complex infighting around the appointment of the new director, and the usual range of crises around serious concerns like office furniture or trivialities like the future of the subject and the balance between publication pressure and quality of research. Meanwhile, as tends to happen more and more when you get to that age, Maarten has to deal with the deaths of friends and family. Voskuil’s strictly chronological narrative continues to tease us with plot threads that get tucked away to be resumed hundreds of pages later when that particular committee has its next meeting. Insanely detailed, but still full of stuff that anyone who has ever worked in a public-service office will be able to identify with.

Afgang (2000) by J J Voskuil (NL, 1926-2008)

The penultimate part of Het Bureau takes us into the mid-1980s, when office life had been changed forever by the invention of the Post-It note and the computer was making inroads even into the humanities and social sciences. Government cuts are still the flavour of the moment, and the Institute seems to be under threat.

Maarten Koning is now in his late fifties, starting to become a little battle-weary, and he declines to apply for the post when his boss for the last twenty years, Jaap Balk, steps down. There’s a lot of complex infighting around the appointment of the new director, and the usual range of crises around serious concerns like office furniture or trivialities like the future of the subject and the balance between publication pressure and quality of research. Meanwhile, as tends to happen more and more when you get to that age, Maarten has to deal with the deaths of friends and family. Voskuil’s strictly chronological narrative continues to tease us with plot threads that get tucked away to be resumed hundreds of pages later when that particular committee has its next meeting. Insanely detailed, but still full of stuff that anyone who has ever worked in a public-service office will be able to identify with.

4thorold

Carrying on with my trek through the back-catalogue of Percival Everett, this was his most successful novel before James. Many other people in CR have read this, but it took me a while to find a copy.

The Trees (2021) by Percival Everett (US, 1956- )

A small town in Mississippi is shocked by a series of brutal killings, where in each case the corpse of an unidentified Black man is found next to the even more badly mutilated body of an unpopular white resident. Bizarrely, it seems to be the same Black man each time, and the body has an odd resemblance to a certain historical photograph. The local sheriff’s office is overwhelmed, and external detectives are sent in from State and Federal forces to assist with the investigation. The locals have to mind their words when it becomes clear that all these outsiders are Black…

As everyone says, it’s a mystery how Everett managed to write a genuinely funny book about lynchings. Part of the answer seems to be Everett’s use of a Swiftian style of satire that exaggerates reality to the point of absurdity and sees absolutely no need to cater to the requirements of good taste, but there’s obviously more to it than that. There was something about the set-up that reminded me oddly of Terry Pratchett’s angrier books — Everett makes the cliché southern small town (and perhaps, by extension, the whole United States and its troubled history of racist violence) into a world as weird and remote from common-sense reality as Pratchett’s Discworld, allowing him to make us laugh at things that would be exceedingly dark and disturbing in any other context.

Of course, there is a serious message behind all the clever literary foolery: Everett is making fun of the right-wing notion of “race war” or “threats to white America” by imagining what those things would look like if they did exist, and he also wants us to understand how much we owe it to the victims of racism and slavery to remember their stories. In some ways, he’s coming to the same point as Toni Morrison, but from a diametrically opposed perspective.

The Trees (2021) by Percival Everett (US, 1956- )

A small town in Mississippi is shocked by a series of brutal killings, where in each case the corpse of an unidentified Black man is found next to the even more badly mutilated body of an unpopular white resident. Bizarrely, it seems to be the same Black man each time, and the body has an odd resemblance to a certain historical photograph. The local sheriff’s office is overwhelmed, and external detectives are sent in from State and Federal forces to assist with the investigation. The locals have to mind their words when it becomes clear that all these outsiders are Black…

As everyone says, it’s a mystery how Everett managed to write a genuinely funny book about lynchings. Part of the answer seems to be Everett’s use of a Swiftian style of satire that exaggerates reality to the point of absurdity and sees absolutely no need to cater to the requirements of good taste, but there’s obviously more to it than that. There was something about the set-up that reminded me oddly of Terry Pratchett’s angrier books — Everett makes the cliché southern small town (and perhaps, by extension, the whole United States and its troubled history of racist violence) into a world as weird and remote from common-sense reality as Pratchett’s Discworld, allowing him to make us laugh at things that would be exceedingly dark and disturbing in any other context.

Of course, there is a serious message behind all the clever literary foolery: Everett is making fun of the right-wing notion of “race war” or “threats to white America” by imagining what those things would look like if they did exist, and he also wants us to understand how much we owe it to the victims of racism and slavery to remember their stories. In some ways, he’s coming to the same point as Toni Morrison, but from a diametrically opposed perspective.

5edwinbcn

>4 thorold: Nice to read a different work from the Booker nominated author and find it holds up well, as a four-star read.

6thorold

This is one I came across whilst scanning shelves with an eye out for something that would fit in with the “island nations” theme. Guadeloupe is an overseas territory of France, not a sovereign nation, of course.

Le coeur à rire et à pleurer (Tales from the heart, 1999) by Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe, 1937-2024)

Maryse Condé’s short childhood memoir describes growing up in a middle-class Black family in Guadeloupe in the 1940s, and follows her experience up to her early years as a student at the Sorbonne. She was the youngest child in a large family: her father was a former civil servant who had become a banker, her mother a teacher, and both of them considered themselves more French than the French. Young Maryse was strictly prohibited from speaking Creole, and only allowed to associate with children “of her own sort” — she talks about her shock at realising on trips to Paris that white people looked down on them and regarded their ability to speak good French as though it was some sort of circus skill they had learnt.

This is a charming account of childhood and the oddities of growing up in a privileged niche protected from the realities of your own culture. You don’t have to read it politically to enjoy it, but of course it is a very political book.

Le coeur à rire et à pleurer (Tales from the heart, 1999) by Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe, 1937-2024)

Maryse Condé’s short childhood memoir describes growing up in a middle-class Black family in Guadeloupe in the 1940s, and follows her experience up to her early years as a student at the Sorbonne. She was the youngest child in a large family: her father was a former civil servant who had become a banker, her mother a teacher, and both of them considered themselves more French than the French. Young Maryse was strictly prohibited from speaking Creole, and only allowed to associate with children “of her own sort” — she talks about her shock at realising on trips to Paris that white people looked down on them and regarded their ability to speak good French as though it was some sort of circus skill they had learnt.

This is a charming account of childhood and the oddities of growing up in a privileged niche protected from the realities of your own culture. You don’t have to read it politically to enjoy it, but of course it is a very political book.

7thorold

A bit of Clevelandiana, since that’s where I am. The city’s history is all about steel making, but it seems to be surprisingly reluctant to tell you anything about that side of itself. A kiss-and-tell about being at the sharp end of the steel industry by someone who is now teaching at John Carroll:

Rust (2020) by Eliese Colette Goldbach (US, 1986- )

(Author photo nypost.com)

Former Cleveland house painter and English graduate Eliese Goldbach describes her three-year spell as a worker in the big AcelorMittal (now Cleveland Cliffs) steel plant in the Cuyahoga valley. During that time she worked in several different areas of the plant. She writes about the hazards of working with hot metals and large and heavy machines, about her interactions with other workers, managers and the union, about the stress of working irregular shifts, and gives a lot of fascinating detail about a world most of us only ever see in a historical context or in clips showing hot metal pouring out of a furnace or ingots going through a roller mill. It clearly looks rather different when you are actually working with it. Goldbach seems to give us a very good sense of what it’s like, and tries to put her finger on what it is that defines the identity of rust-belt industrial workers in the 21st century.

Oddly, the element of the book I was expecting to find most interesting — what it’s like to work in the traditionally male world of heavy industry as a woman — doesn’t really come off. Other people had fought the real battles before Goldbach got there, and she seems to have found that what was needed to survive was a bit of a tough attitude and a readiness to swear at people who annoyed her. I imagine that a male college graduate would have experienced much the same.

Goldbach weaves into the story an outline memoir of her earlier life, dealing with her Catholic, Republican upbringing in a working-class family on Cleveland’s West Side, her experience of date-rape at what sounds like a third-rate Catholic university, and her later struggles with mental illness and boyfriend troubles. All very worthy, and her candour about her problems obviously does her credit, but it somehow all feels a bit routine. What she has to say about her work experience writes itself, because there simply aren’t all that many firsthand accounts by intelligent people about contemporary industrial work. But what she says about her personal life somehow struggles to maintain the level of a mediocre novel.

Rust (2020) by Eliese Colette Goldbach (US, 1986- )

(Author photo nypost.com)

Former Cleveland house painter and English graduate Eliese Goldbach describes her three-year spell as a worker in the big AcelorMittal (now Cleveland Cliffs) steel plant in the Cuyahoga valley. During that time she worked in several different areas of the plant. She writes about the hazards of working with hot metals and large and heavy machines, about her interactions with other workers, managers and the union, about the stress of working irregular shifts, and gives a lot of fascinating detail about a world most of us only ever see in a historical context or in clips showing hot metal pouring out of a furnace or ingots going through a roller mill. It clearly looks rather different when you are actually working with it. Goldbach seems to give us a very good sense of what it’s like, and tries to put her finger on what it is that defines the identity of rust-belt industrial workers in the 21st century.

Oddly, the element of the book I was expecting to find most interesting — what it’s like to work in the traditionally male world of heavy industry as a woman — doesn’t really come off. Other people had fought the real battles before Goldbach got there, and she seems to have found that what was needed to survive was a bit of a tough attitude and a readiness to swear at people who annoyed her. I imagine that a male college graduate would have experienced much the same.

Goldbach weaves into the story an outline memoir of her earlier life, dealing with her Catholic, Republican upbringing in a working-class family on Cleveland’s West Side, her experience of date-rape at what sounds like a third-rate Catholic university, and her later struggles with mental illness and boyfriend troubles. All very worthy, and her candour about her problems obviously does her credit, but it somehow all feels a bit routine. What she has to say about her work experience writes itself, because there simply aren’t all that many firsthand accounts by intelligent people about contemporary industrial work. But what she says about her personal life somehow struggles to maintain the level of a mediocre novel.

8thorold

Some French crime:

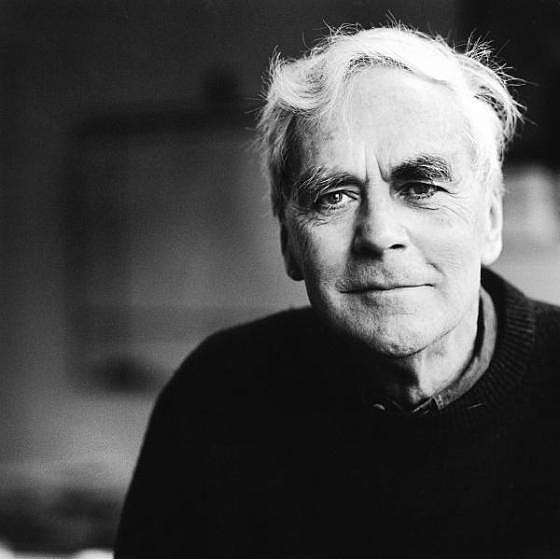

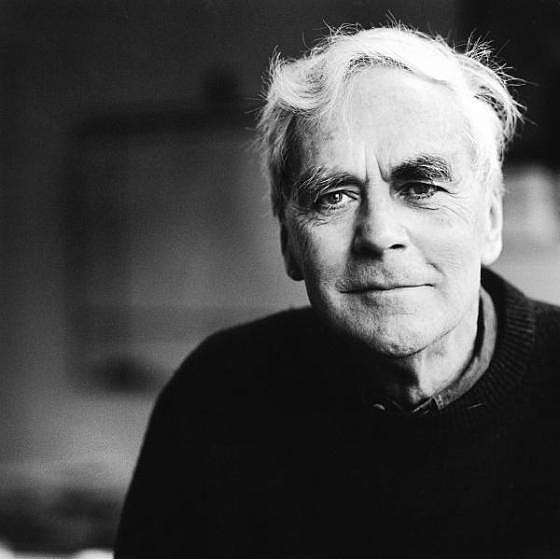

Morgue pleine (No room at the morgue, 1973) by Jean-Patrick Manchette (France, 1942-1995)

Ex-cop Eugène Tarpon is on the point of giving up his ailing private eye business in Paris and going home to mother when … yes, you guessed it, a beautiful young woman appears in his office late at night, seeking his help. But this is a second-generation French noir story, so he tells her to go away and talk to the cops instead. Needless to say, he reconsiders a few hours later, and soon finds himself mixed up in a colourful and confusing story involving starlets, would-be urban guerrillas, foreign agents and American gangsters. And a fair assortment of corpses, as the title implies.

Manchette provides a fast-moving narrative that refuses to take itself seriously, simultaneously exploiting the conventions of classic noir and making fun of them. Tarpon is an uncharacteristic private eye, by fictional standards: a former rank-and-file gendarme who couldn‘t face staying in the force after inadvertently killing a protester during a demonstration, he seems to spend a lot of his time overwhelmed by the mess he’s fallen into. Without his chance sidekick, the retired journalist Haymann, it’s hard to imagine him investigating anything more serious than a straying spouse. But then occasionally his reflexes seem to lead him lightning fast out of difficult situations. Good fun, despite the piles of corpses.

Morgue pleine (No room at the morgue, 1973) by Jean-Patrick Manchette (France, 1942-1995)

Ex-cop Eugène Tarpon is on the point of giving up his ailing private eye business in Paris and going home to mother when … yes, you guessed it, a beautiful young woman appears in his office late at night, seeking his help. But this is a second-generation French noir story, so he tells her to go away and talk to the cops instead. Needless to say, he reconsiders a few hours later, and soon finds himself mixed up in a colourful and confusing story involving starlets, would-be urban guerrillas, foreign agents and American gangsters. And a fair assortment of corpses, as the title implies.

Manchette provides a fast-moving narrative that refuses to take itself seriously, simultaneously exploiting the conventions of classic noir and making fun of them. Tarpon is an uncharacteristic private eye, by fictional standards: a former rank-and-file gendarme who couldn‘t face staying in the force after inadvertently killing a protester during a demonstration, he seems to spend a lot of his time overwhelmed by the mess he’s fallen into. Without his chance sidekick, the retired journalist Haymann, it’s hard to imagine him investigating anything more serious than a straying spouse. But then occasionally his reflexes seem to lead him lightning fast out of difficult situations. Good fun, despite the piles of corpses.

9SassyLassy

>8 thorold: That was a fun book.

Don't think I have seen a photo of Manchette before, and. somehow the image and his books don't quite go together in my mind.

Don't think I have seen a photo of Manchette before, and. somehow the image and his books don't quite go together in my mind.

10thorold

>9 SassyLassy: Yes!

In pictures, he always seems to have that air of someone who was just slightly too jolly and slightly too chubby to be one of the really cool kids in the seventies; from the books you’d expect something a bit more in the reformed juvenile delinquent mode.

There’s a nice interview with him a little bit later in life here:

https://youtu.be/m8bVoEp1FOk — sitting on his couch in his forties he seems to have something of the air of an off-duty truck driver, but what he has to say certainly sounds like the voice of his books.

In pictures, he always seems to have that air of someone who was just slightly too jolly and slightly too chubby to be one of the really cool kids in the seventies; from the books you’d expect something a bit more in the reformed juvenile delinquent mode.

There’s a nice interview with him a little bit later in life here:

https://youtu.be/m8bVoEp1FOk — sitting on his couch in his forties he seems to have something of the air of an off-duty truck driver, but what he has to say certainly sounds like the voice of his books.

11thorold

Not sure why I had this one on my e-reader, but I did have a phase of books about borders a year or two ago, so it might be left over from that. Crofton is a former publisher who has written a lot of miscellaneous — mostly history-based — non-fiction over the years. Apparently he was born in Scotland but has lived most of his life in England.

Walking the Border (2014) by Ian Crofton (UK, - )

Until about three hundred years ago, the border between England and Scotland was a place of frequent official and unofficial violence. In the brief intervals when England and Scotland were not at war, local chieftains amused themselves and kept the ballad industry afloat by stealing each others’ cattle or women, or simply rode out to take revenge for an earlier raid. Happily, that’s all a thing of the past. But, as Crofton pursues his walk along this arbitrary and rather confusing line on the map from Solway to Tweed, with a Scottish independence referendum on the horizon, he is forced to wonder about the meaning of borders in a place where there is no essential difference in language, culture, or anything else between the people living on one side of the line and those on the other. Borderers may be quite different from people who live in southern England or the Scottish central belt, but they are very much like each other, and most of them seem to have personal and family connections on both sides of the line.

A fun little book, with some nice photographs, but it’s not a walking route anyone’s likely to want to reproduce. There are few sections of the border that follow roads or footpaths, so Crofton mostly has to contend with the tedious business of walking off-piste in northern Britain, which always involves a lot of rough ground, endless bogs, barbed wire fences, drystone walls, and angry bullocks. Plus, when he’s on the English side of the border, the risk of being sued for trespass by indignant landowners.

Walking the Border (2014) by Ian Crofton (UK, - )

Until about three hundred years ago, the border between England and Scotland was a place of frequent official and unofficial violence. In the brief intervals when England and Scotland were not at war, local chieftains amused themselves and kept the ballad industry afloat by stealing each others’ cattle or women, or simply rode out to take revenge for an earlier raid. Happily, that’s all a thing of the past. But, as Crofton pursues his walk along this arbitrary and rather confusing line on the map from Solway to Tweed, with a Scottish independence referendum on the horizon, he is forced to wonder about the meaning of borders in a place where there is no essential difference in language, culture, or anything else between the people living on one side of the line and those on the other. Borderers may be quite different from people who live in southern England or the Scottish central belt, but they are very much like each other, and most of them seem to have personal and family connections on both sides of the line.

A fun little book, with some nice photographs, but it’s not a walking route anyone’s likely to want to reproduce. There are few sections of the border that follow roads or footpaths, so Crofton mostly has to contend with the tedious business of walking off-piste in northern Britain, which always involves a lot of rough ground, endless bogs, barbed wire fences, drystone walls, and angry bullocks. Plus, when he’s on the English side of the border, the risk of being sued for trespass by indignant landowners.

12thorold

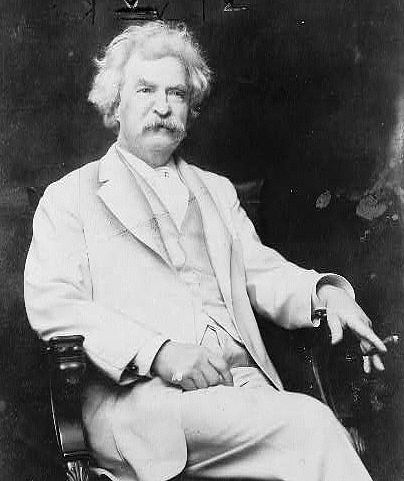

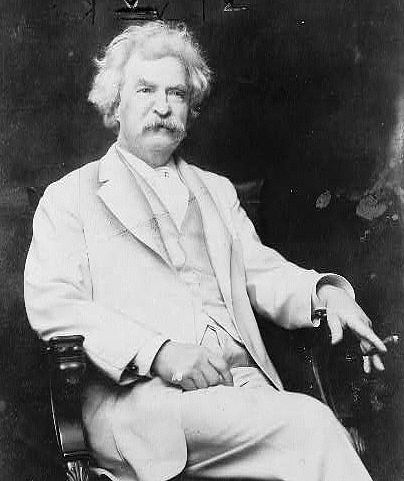

A little bit of Mark Twain I hadn’t come across before:

The Diary of Adam and Eve: and other Adamic Stories (1893-1906;2002) by Mark Twain (USA, 1835-1910)

This little Hesperus Press edition brings together various pieces written by Mark Twain towards the end of his life, making fun of the Biblical creation stories through the voices of Adam and Eve. Some of these were originally published during Twain’s lifetime in The $30,000 Bequest and other stories (1906), others are posthumous. Bizarrely, the first piece, “Extracts from Adam’s diary” originally appeared in a souvenir book for the 1893 World’s Fair in Buffalo, NY — Twain seems to have doctored an earlier, discarded text by throwing in a lot of references to Niagara Falls, apparently the site of the original Garden of Eden.

Twain has a lot of (mildly sexist) fun imagining how much it would annoy prelapsarian Adam to have “this new creature with the long hair” continually talking at him and interfering with his notion that there should be six Sundays and one working day in the week — postlapsarian Adam of course learns to enjoy her companionship and misses her when she’s gone. Twain also enjoys himself pondering the absurdities of the Garden with its vegetarian, pacifist lions and tigers, whose teeth Eve inspects and declares to have been designed for ripping flesh, not for munching grass and fruit. And we have fun with Adam and Eve both trying to work out what manner of creatures the young Cain and Abel might be.

In another piece Twain (via Eve, at the age of 920) does the maths to show us how the world’s population, before the introduction of death from old age, would have reached an unsustainable level of 5 billion within her lifetime: only war, famine and pestilence had kept the planet from disaster. Elsewhere again, Adam interrogates Noah to establish how the dinosaurs got left off the Ark.

Nothing very profound — Twain is basically just working up the idiocies that most intelligent readers notice the first time they look at the stories in Genesis into elaborate and slightly cumbersome jokes. But quite enjoyable, even a century later.

The Diary of Adam and Eve: and other Adamic Stories (1893-1906;2002) by Mark Twain (USA, 1835-1910)

This little Hesperus Press edition brings together various pieces written by Mark Twain towards the end of his life, making fun of the Biblical creation stories through the voices of Adam and Eve. Some of these were originally published during Twain’s lifetime in The $30,000 Bequest and other stories (1906), others are posthumous. Bizarrely, the first piece, “Extracts from Adam’s diary” originally appeared in a souvenir book for the 1893 World’s Fair in Buffalo, NY — Twain seems to have doctored an earlier, discarded text by throwing in a lot of references to Niagara Falls, apparently the site of the original Garden of Eden.

Twain has a lot of (mildly sexist) fun imagining how much it would annoy prelapsarian Adam to have “this new creature with the long hair” continually talking at him and interfering with his notion that there should be six Sundays and one working day in the week — postlapsarian Adam of course learns to enjoy her companionship and misses her when she’s gone. Twain also enjoys himself pondering the absurdities of the Garden with its vegetarian, pacifist lions and tigers, whose teeth Eve inspects and declares to have been designed for ripping flesh, not for munching grass and fruit. And we have fun with Adam and Eve both trying to work out what manner of creatures the young Cain and Abel might be.

In another piece Twain (via Eve, at the age of 920) does the maths to show us how the world’s population, before the introduction of death from old age, would have reached an unsustainable level of 5 billion within her lifetime: only war, famine and pestilence had kept the planet from disaster. Elsewhere again, Adam interrogates Noah to establish how the dinosaurs got left off the Ark.

Nothing very profound — Twain is basically just working up the idiocies that most intelligent readers notice the first time they look at the stories in Genesis into elaborate and slightly cumbersome jokes. But quite enjoyable, even a century later.

13labfs39

I found The Diary of Adam and Eve to be laugh out loud funny. I didn't realize there were other stories in a related vein. I'll look for them.

14cindydavid4

>4 thorold: I didnt think a book could be as good as James until I read the trees You are right about it being very much Swiftian, as well as more than a little bit of Pratchett. I cant remember the exact quote, but the character who is typing the names, ends up erasing them, in order to free them had me in tears. Im thinking I will need to reread it soon

15cindydavid4

>6 thorold: I chose this book to read for the Islands theme and liking it quite a bit Didnt realize she also wrote I,Tituba, Black Witch of Salem Read it ages ago and found it fascinating to compare it with the character of the crucible that we did HS. and realized how little we really know about her

16thorold

>14 cindydavid4: Yes, it could well have been that idea about the power of typing the names that made me think of Pratchett, although now I come to think of it there’s also a very similar thing in Trieste by Daša Drndić, which is a very serious novel.

On to the book I read on the plane journey back to Holland from Cleveland. I loved The lost language of cranes, something I’ve frequently regretted when it’s made me read one of David Leavitt’s more recent novels…

Shelter in Place (2020) by David Leavitt (USA, 1961- )

This has a very promising opening, with a bunch of New York middle-class liberals at a party in early November 2016 discussing whether emigration or political assassination would be the most appropriate response to America’s latest self-inflicted disaster. It looks as though we’re in for a bright, Firbankian political satire of Trump-era life, something that would take our minds off the current nervous speculation about whether anyone could be crazy enough to vote for him a second time (written late October 2024).

But unfortunately, the book doesn’t really deliver on this early promise. It turns into a rather rambling adultery comedy, rather like a less-funny version of Ab Fab, in which the only real joke is the way the overprivileged characters constantly fail to realise that their worthy political ideals are undermined by the financial security blanket that insulates their lives from the consequences of the actions of even the most incompetent and self-interested administration. The only real whiff of the old Leavitt is the gay interior designer (hold on a minute: a gay interior designer? What next, flight attendants…?) Jake, who turns out to have a much-trailed-but-only-revealed-in-the-last-chapter back-story that could well have been the main plot of a Leavitt novel in the 1980s. Good in parts, but it felt like a waste of a situation that he could have done so much more with.

On to the book I read on the plane journey back to Holland from Cleveland. I loved The lost language of cranes, something I’ve frequently regretted when it’s made me read one of David Leavitt’s more recent novels…

Shelter in Place (2020) by David Leavitt (USA, 1961- )

This has a very promising opening, with a bunch of New York middle-class liberals at a party in early November 2016 discussing whether emigration or political assassination would be the most appropriate response to America’s latest self-inflicted disaster. It looks as though we’re in for a bright, Firbankian political satire of Trump-era life, something that would take our minds off the current nervous speculation about whether anyone could be crazy enough to vote for him a second time (written late October 2024).

But unfortunately, the book doesn’t really deliver on this early promise. It turns into a rather rambling adultery comedy, rather like a less-funny version of Ab Fab, in which the only real joke is the way the overprivileged characters constantly fail to realise that their worthy political ideals are undermined by the financial security blanket that insulates their lives from the consequences of the actions of even the most incompetent and self-interested administration. The only real whiff of the old Leavitt is the gay interior designer (hold on a minute: a gay interior designer? What next, flight attendants…?) Jake, who turns out to have a much-trailed-but-only-revealed-in-the-last-chapter back-story that could well have been the main plot of a Leavitt novel in the 1980s. Good in parts, but it felt like a waste of a situation that he could have done so much more with.

17thorold

If >16 thorold: was an attempt by an established gay writer to get away from the old formulas, this next one is almost the opposite:

Tiepolo Blue (2022) by James Cahill (UK, - )

(Author photo by Edwardx, via Wikipedia)

When I picked this off the shelf, I thought it must be a reissue of a forgotten gay classic from way back: with the Hockneyesque swimming pool on the front cover, the catalogue of endorsements by everyone from Ed White to Stephen Fry, and the jerky plot about a deeply-closeted academic discovering the gay scene in nineties London, it had all the hallmarks of something that had originally come out in a small and typo-ridden print run almost all of which ended up in a skip behind Gay’s The Word. But it turns out to be a new first novel by a British art historian who can scarcely be old enough to have known nineties London himself. Very odd.

I wanted to enjoy this, and I mostly did, although it wasn’t very obvious what Cahill was trying to achieve apart from nostalgia and a lot of in-jokes about the fine-art world. It’s stylish, literate and full of nice bits of observation, but it’s a little bit too heavy in its hints at all the things that our naive professor is failing to pick up about the world around him, and that does make you want to reach out for the fast-forward button sometimes. If it’s really the best novel Stephen Fry has read for ages, he needs to freshen up his book-pile a bit.

— — —

(Bizarrely, it turns out that the other author called James Cahill is also an art historian, albeit an American one who died ten years ago.)

Tiepolo Blue (2022) by James Cahill (UK, - )

(Author photo by Edwardx, via Wikipedia)

When I picked this off the shelf, I thought it must be a reissue of a forgotten gay classic from way back: with the Hockneyesque swimming pool on the front cover, the catalogue of endorsements by everyone from Ed White to Stephen Fry, and the jerky plot about a deeply-closeted academic discovering the gay scene in nineties London, it had all the hallmarks of something that had originally come out in a small and typo-ridden print run almost all of which ended up in a skip behind Gay’s The Word. But it turns out to be a new first novel by a British art historian who can scarcely be old enough to have known nineties London himself. Very odd.

I wanted to enjoy this, and I mostly did, although it wasn’t very obvious what Cahill was trying to achieve apart from nostalgia and a lot of in-jokes about the fine-art world. It’s stylish, literate and full of nice bits of observation, but it’s a little bit too heavy in its hints at all the things that our naive professor is failing to pick up about the world around him, and that does make you want to reach out for the fast-forward button sometimes. If it’s really the best novel Stephen Fry has read for ages, he needs to freshen up his book-pile a bit.

— — —

(Bizarrely, it turns out that the other author called James Cahill is also an art historian, albeit an American one who died ten years ago.)

18thorold

New distractions are piling up on the TBR: this year’s new novels by Ali Smith and Alan Hollinghurst came in today, and the new Jonathan Coe should be here shortly… Before I get onto those, time to revisit the World Tour, which has been rather neglected lately. Next stop: Chile. And whom have we heard of in Chile…?

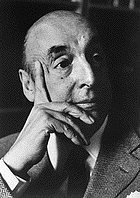

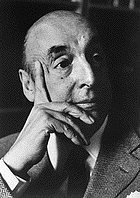

This is a book I picked up from the formidable poetry section upstairs in City Lights when I was in San Francisco last year. It’s one of their own publications, of course.

The essential Neruda (2004) by Pablo Neruda (Chile, 1904-1973), edited by Mark Eisner

(Editor photo from www.markeisner.net )

Neruda is everyone’s idea of what a poet should be like: passionate, romantic, extravagant, and colourful; a lot of his poems are about sex or politics, and he spent a good bit of his life in exile. His free-form rants and often surreal leaps of language spoke to people like the Beats (hence this collection edited by Mark Eisner for City Lights to mark the centenary of Neruda’s birth), but there is also plenty in his work to appeal to more everyday readers. If you’re a sex-starved teenager or an oppressed worker, there is something here for you.

All these things rather put me off reading Neruda for a long time — like Byron, knowing about him seems almost more interesting than actually reading him — but I’ve been slowly dipping toes in his work for the last couple of years. This selection of work from across a big part of his career comes with new or revised parallel-text translations by Eisner and seven of his colleagues (the translator of each poem is identified by initials: I love the way this means that all the poems Eisner did himself are signed “ME”!). We go from the early Canto General and Veinte poemas de amor to later, more reflective works. I was particularly struck by the selections from Odas elementales, where he focuses down onto very simple concepts — a chestnut, a book, a watch, a glass of wine — something quite surprising when you are used to his usual more bombastic style.

Interesting, reading this in late October, to realise what a poet of autumn he is — autumnal images come up almost as often in his poems as sea-images. Maybe unexpected too, when you reflect on how he moved between hemispheres during his life. Sometimes he almost seems more of a Keats than a Byron!

This is a book I picked up from the formidable poetry section upstairs in City Lights when I was in San Francisco last year. It’s one of their own publications, of course.

The essential Neruda (2004) by Pablo Neruda (Chile, 1904-1973), edited by Mark Eisner

(Editor photo from www.markeisner.net )

Neruda is everyone’s idea of what a poet should be like: passionate, romantic, extravagant, and colourful; a lot of his poems are about sex or politics, and he spent a good bit of his life in exile. His free-form rants and often surreal leaps of language spoke to people like the Beats (hence this collection edited by Mark Eisner for City Lights to mark the centenary of Neruda’s birth), but there is also plenty in his work to appeal to more everyday readers. If you’re a sex-starved teenager or an oppressed worker, there is something here for you.

All these things rather put me off reading Neruda for a long time — like Byron, knowing about him seems almost more interesting than actually reading him — but I’ve been slowly dipping toes in his work for the last couple of years. This selection of work from across a big part of his career comes with new or revised parallel-text translations by Eisner and seven of his colleagues (the translator of each poem is identified by initials: I love the way this means that all the poems Eisner did himself are signed “ME”!). We go from the early Canto General and Veinte poemas de amor to later, more reflective works. I was particularly struck by the selections from Odas elementales, where he focuses down onto very simple concepts — a chestnut, a book, a watch, a glass of wine — something quite surprising when you are used to his usual more bombastic style.

Interesting, reading this in late October, to realise what a poet of autumn he is — autumnal images come up almost as often in his poems as sea-images. Maybe unexpected too, when you reflect on how he moved between hemispheres during his life. Sometimes he almost seems more of a Keats than a Byron!

Y que metí la cuchara hasta el codo

en una adversidad que no era mía,

en el padecimiento de los otros.

No se trató de palma o de partido

sino de poca cosa: no poder

vivir ni respirar con esa sombra,

con esa sombra de otros como torres,

como árboles amargos que lo entierran,

como golpes de piedra en las rodillas.

I plunged up to the neck

into adversities that were not mine,

into all the sufferings of others.

It wasn't a question of applause or profit.

Much less. It was not being able

to live or breathe in this shadow,

the shadow of others like towers,

like bitter trees that bury you,

like cobblestones on the knees.

(From “October Fullness”, trans. Alastair Reid)

19thorold

And, right off the top of the pile, the new Ali Smith…

Gliff (2024-10-31) by Ali Smith (UK, 1962- )

If there’s a dystopia to be written about, then for Ali Smith it’s essentially the place where we already live, with its data centres and camera surveillance and the murky giant corporations that seem to do all kinds of other ill-defined things besides their ostensible roles in making household chemicals and pharmaceuticals, delivering parcels, or providing security guards for us.

In this reworking of Brave New World (with a few shovelfuls of Black Beauty), two children — sometimes assisted by a horse and an elusive old lady — find themselves trapped on the outside of the data society after a mysterious red line is drawn around their house, and are inspired into a gesture of resistance. Smith riffs on her usual topics, like the power of words and of the ability to name things (and ourselves) as we choose, the importance of community and spontaneity, and the subversive capacity of books. Powerful stuff, as ever, but she seems to be getting a shade or two darker with each book. Or is the world simply getting worse?

- - -

The vignette on the cover is a detail from a Dora Carrington painting, Iris Tree on a horse

Gliff (2024-10-31) by Ali Smith (UK, 1962- )

If there’s a dystopia to be written about, then for Ali Smith it’s essentially the place where we already live, with its data centres and camera surveillance and the murky giant corporations that seem to do all kinds of other ill-defined things besides their ostensible roles in making household chemicals and pharmaceuticals, delivering parcels, or providing security guards for us.

In this reworking of Brave New World (with a few shovelfuls of Black Beauty), two children — sometimes assisted by a horse and an elusive old lady — find themselves trapped on the outside of the data society after a mysterious red line is drawn around their house, and are inspired into a gesture of resistance. Smith riffs on her usual topics, like the power of words and of the ability to name things (and ourselves) as we choose, the importance of community and spontaneity, and the subversive capacity of books. Powerful stuff, as ever, but she seems to be getting a shade or two darker with each book. Or is the world simply getting worse?

- - -

The vignette on the cover is a detail from a Dora Carrington painting, Iris Tree on a horse

20labfs39

>19 thorold: Great review. I am tempted to try this as it sounds very different from her seasons quartet, which I gave up on after the second book. Powerful stuff, as ever, but she seems to be getting a shade or two darker with each book. Or is the world simply getting worse? I'll let you know next week...

21thorold

>20 labfs39: Thanks! I don’t know if you’ll find it that different from the Seasons, but I’ll be interested to know how you get on!

A lot of distractions over the last week, but I’ve just made it through another hefty recent publication. MacCulloch is emeritus professor of Church History in Oxford. You might have seen the BBC series on the history of Christianity he did about ten years ago.

Lower than the Angels: a history of sex and Christianity (2024) by Diarmaid MacCulloch (UK, 1951- )

As the author warns us, this is a subject where the reader inevitably brings along a certain amount of baggage. If you didn‘t have strong views, you wouldn’t be here. MacCulloch goes out of his way to avoid treading on our toes during this three-thousand-year jog through the more prurient sides of ecclesiastical history, with the inevitable result that we start to get frustrated with his calm refusal to mock or condemn anybody’s standpoint, however absurd or closed-minded it seems to us in hindsight.

On the other hand, he does take us smoothly through an awful lot of material, clearing up a lot of misconceptions along the way. It becomes very clear that Christianity as a whole has never had a single, consistent teaching on human sexuality. At one time or another, just about anything we might do with our genitals (or to them — cf. Origen) has been condemned by some theologians and licensed by others. Christians have sought to apply the very fragmentary and contradictory teachings found in the Bible to the times they are living in, and come up with what often feels like a baffling range of different answers. Some of these proved to be impractical or destructive, and were quickly discarded, others met the needs of ordinary Christians or the church authorities in some way and embedded themselves in the fabric of ecclesiastical reality for longer or shorter periods of time. Monogamy, for instance, was an innovation adopted to meet social expectations when the church first expanded from West Asia into the main part of the Roman Empire, but stuck, and has only very occasionally been challenged since then (e.g. by the Mormons or by some 20th century African churches).

Obviously, in a book that takes us all the way from Old Testament Judaism to Putin and Patriarch Kirill, we have to spend a lot of time in the Middle Ages and don’t get to look at events in our own lifetime in as much detail as we might like, but there are plenty of other sources for that, and MacCulloch provides us with a comprehensive bibliography. An interesting, useful and quite lively book, even if it does engender the occasional fit of rage…

A lot of distractions over the last week, but I’ve just made it through another hefty recent publication. MacCulloch is emeritus professor of Church History in Oxford. You might have seen the BBC series on the history of Christianity he did about ten years ago.

Lower than the Angels: a history of sex and Christianity (2024) by Diarmaid MacCulloch (UK, 1951- )

Anyone sitting down to read a history of sex and Christianity in the twenty-first century is likely to have one reason or another for being in a rage. This book will serve as a receptacle for an impressively contradictory range of furies. It will displease those confident that they can find a consistent view on sex in a seamless and infallible text known as the Bible, or those who with equal confidence believe that a single true Church has preached a timeless message on the subject. Others will bring experiences leading them to hate Christianity as a vehicle of oppression and trauma in sexual matters, and they may be dissatisfied with a story that tries to avoid caricaturing the past.

As the author warns us, this is a subject where the reader inevitably brings along a certain amount of baggage. If you didn‘t have strong views, you wouldn’t be here. MacCulloch goes out of his way to avoid treading on our toes during this three-thousand-year jog through the more prurient sides of ecclesiastical history, with the inevitable result that we start to get frustrated with his calm refusal to mock or condemn anybody’s standpoint, however absurd or closed-minded it seems to us in hindsight.

On the other hand, he does take us smoothly through an awful lot of material, clearing up a lot of misconceptions along the way. It becomes very clear that Christianity as a whole has never had a single, consistent teaching on human sexuality. At one time or another, just about anything we might do with our genitals (or to them — cf. Origen) has been condemned by some theologians and licensed by others. Christians have sought to apply the very fragmentary and contradictory teachings found in the Bible to the times they are living in, and come up with what often feels like a baffling range of different answers. Some of these proved to be impractical or destructive, and were quickly discarded, others met the needs of ordinary Christians or the church authorities in some way and embedded themselves in the fabric of ecclesiastical reality for longer or shorter periods of time. Monogamy, for instance, was an innovation adopted to meet social expectations when the church first expanded from West Asia into the main part of the Roman Empire, but stuck, and has only very occasionally been challenged since then (e.g. by the Mormons or by some 20th century African churches).

Obviously, in a book that takes us all the way from Old Testament Judaism to Putin and Patriarch Kirill, we have to spend a lot of time in the Middle Ages and don’t get to look at events in our own lifetime in as much detail as we might like, but there are plenty of other sources for that, and MacCulloch provides us with a comprehensive bibliography. An interesting, useful and quite lively book, even if it does engender the occasional fit of rage…

22labfs39

>21 thorold: I rarely think to give thumbs these days, but this review prompted me to take the time to do so. Your reviews are always so well-written, but some pique my interest or make me laugh. I'm thankful to have your reviews to help me judge whether a book is for me.

23thorold

>22 labfs39: Well, it’s not often that the author himself supplies the perfect introductory paragraph for your review!

24thorold

Another new release that has just come in:

The Proof of My Innocence (2024-11-07) by Jonathan Coe (UK, 1961- )

Jonathan Coe is back, chronicling Britain during the Liz Truss Era — presumably this will have to be the first of another long series... And yes, there are lettuce references, but that’s only the tip of the iceberg (sorry!). This is a novel that asks serious questions about the nature and purpose of fiction and digs into how we opened the door to the “selfishness is good” virus of neo-conservatism in the 1980s, represented here by a sinister right-wing think tank centred around a Cambridge philosophy don with more than a passing resemblance to Mrs Thatcher’s Svengali Roger Scruton.

But it’s also a deeply playful postmodern literary gymnasium, chockablock with meaningful ambiguity (I didn’t count, but something tells me there are at least seven types here), whose three sections elegantly parody and subvert three important contemporary genres: cozy mystery, dark academia, and auto-fiction, in turn. A literary puzzle gets tangled up with political plots, and there’s a choice of possible murders. Some readers will probably find this deeply irritating, but it’s extremely well done, and I had a lot of fun reading it. If you enjoyed What a carve up, then this is for you.

The Proof of My Innocence (2024-11-07) by Jonathan Coe (UK, 1961- )

Jonathan Coe is back, chronicling Britain during the Liz Truss Era — presumably this will have to be the first of another long series... And yes, there are lettuce references, but that’s only the tip of the iceberg (sorry!). This is a novel that asks serious questions about the nature and purpose of fiction and digs into how we opened the door to the “selfishness is good” virus of neo-conservatism in the 1980s, represented here by a sinister right-wing think tank centred around a Cambridge philosophy don with more than a passing resemblance to Mrs Thatcher’s Svengali Roger Scruton.

But it’s also a deeply playful postmodern literary gymnasium, chockablock with meaningful ambiguity (I didn’t count, but something tells me there are at least seven types here), whose three sections elegantly parody and subvert three important contemporary genres: cozy mystery, dark academia, and auto-fiction, in turn. A literary puzzle gets tangled up with political plots, and there’s a choice of possible murders. Some readers will probably find this deeply irritating, but it’s extremely well done, and I had a lot of fun reading it. If you enjoyed What a carve up, then this is for you.

25thorold

Blast from the past discovered in one of our local little free libraries. I don’t think I’ve read this since about 1980.

Riotous Assembly (1971) by Tom Sharpe (UK, 1928-2013)

Tom Sharpe’s bawdy comic novels — usually featuring hapless technical college lecturers and inflatable sex toys — were a familiar feature of station bookstalls in the 1970s and 80s, with their iconic cover art by Paul Sample. Of course, they were always written in the worst possible taste, aiming to give offence to as large as possible a segment of the reading public. And we all loved them, largely because Sharpe was a very skilful and precise writer, who could make the English language do exactly what he wanted it to, even in the middle of the most outlandish Grand Guignol Set piece. He is often compared to P G Wodehouse (they were pen-pals and big fans of each other’s work) and Evelyn Waugh: in both cases it’s a comparison that makes a lot of sense, in spite of the big differences in their choice of subject-matter.

What it’s easy to forget is that Sharpe, whose mother was from South Africa, began his literary career in reaction to the horrors of apartheid, which he’d observed while working in Natal. His first play earned him jail time and a permanent ban from entering South Africa, and he followed it with two grotesque satirical novels about the South African police. Riotous assembly, written in a three-week fit of anger, was the first of these. At the heart of the story is Kommandant van Heerden, the incompetent police chief of the sleepy provincial town of Piemburg (a thinly disguised version of Pietermaritzburg, where Sharpe worked for some years). When Miss Hazelstone, doyenne of the surviving British community in Piemburg, calls in to report that she has murdered her Zulu cook in a fit of sexual jealousy, the Anglophile van Heerden takes steps intended to avoid a scandal, but his unclear orders to his demented subordinates lead to an appalling bloodbath. And, naturally enough, all their efforts to tidy the situation up again just make things worse.

As with all over the top satire, you have to wonder how effective it could ever have been. Sharpe is absolutely merciless with his policemen, and makes it pretty clear to us that everything that goes wrong here is the result of them acting on their demented racist assumptions about how the world should be, but he is so very cruel to them that we almost start to feel sympathy with their plight. And the situations are so absurd that they don’t really seem to be telling us much about the realities of life in South Africa at the time. I don’t suppose many people who read this book were supporters of apartheid waiting for Sharpe to convince them to change their minds, anyway.

Riotous Assembly (1971) by Tom Sharpe (UK, 1928-2013)

Tom Sharpe’s bawdy comic novels — usually featuring hapless technical college lecturers and inflatable sex toys — were a familiar feature of station bookstalls in the 1970s and 80s, with their iconic cover art by Paul Sample. Of course, they were always written in the worst possible taste, aiming to give offence to as large as possible a segment of the reading public. And we all loved them, largely because Sharpe was a very skilful and precise writer, who could make the English language do exactly what he wanted it to, even in the middle of the most outlandish Grand Guignol Set piece. He is often compared to P G Wodehouse (they were pen-pals and big fans of each other’s work) and Evelyn Waugh: in both cases it’s a comparison that makes a lot of sense, in spite of the big differences in their choice of subject-matter.

What it’s easy to forget is that Sharpe, whose mother was from South Africa, began his literary career in reaction to the horrors of apartheid, which he’d observed while working in Natal. His first play earned him jail time and a permanent ban from entering South Africa, and he followed it with two grotesque satirical novels about the South African police. Riotous assembly, written in a three-week fit of anger, was the first of these. At the heart of the story is Kommandant van Heerden, the incompetent police chief of the sleepy provincial town of Piemburg (a thinly disguised version of Pietermaritzburg, where Sharpe worked for some years). When Miss Hazelstone, doyenne of the surviving British community in Piemburg, calls in to report that she has murdered her Zulu cook in a fit of sexual jealousy, the Anglophile van Heerden takes steps intended to avoid a scandal, but his unclear orders to his demented subordinates lead to an appalling bloodbath. And, naturally enough, all their efforts to tidy the situation up again just make things worse.

As with all over the top satire, you have to wonder how effective it could ever have been. Sharpe is absolutely merciless with his policemen, and makes it pretty clear to us that everything that goes wrong here is the result of them acting on their demented racist assumptions about how the world should be, but he is so very cruel to them that we almost start to feel sympathy with their plight. And the situations are so absurd that they don’t really seem to be telling us much about the realities of life in South Africa at the time. I don’t suppose many people who read this book were supporters of apartheid waiting for Sharpe to convince them to change their minds, anyway.

26dchaikin

>24 thorold: fun plaque

>25 thorold: is this humor (the book, not your review)? Anyway very interesting life story of Tom Sharpe - who I have never heard of.

Eta

>21 thorold: i thumbed this one too! 👍

>22 labfs39: the first review i’ve read of Gliff. Not sure how i feel about Smith getting darker.

>4 thorold: wonderful review of The Trees.

>25 thorold: is this humor (the book, not your review)? Anyway very interesting life story of Tom Sharpe - who I have never heard of.

Eta

>21 thorold: i thumbed this one too! 👍

>22 labfs39: the first review i’ve read of Gliff. Not sure how i feel about Smith getting darker.

>4 thorold: wonderful review of The Trees.

27thorold

>26 dchaikin: Interesting — sounds as though he didn’t make much impact in the US. Probably not surprising, a very British kind of humour. And very much of its time. I don’t think people coming to it for the first time nowadays would find it very funny.

28thorold

Somehow, almost all the living British writers I follow keenly have been releasing new novels this autumn. Here’s the next one from my pile:

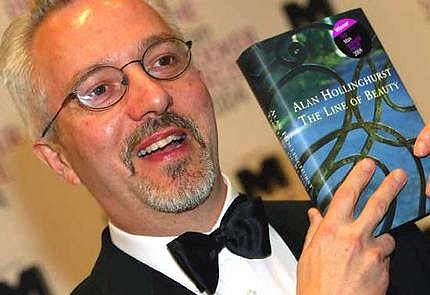

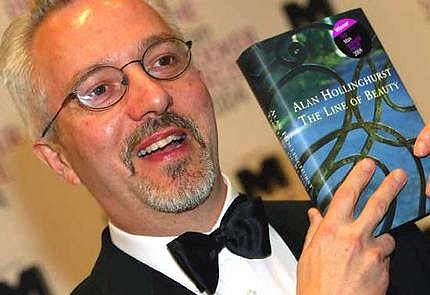

Our Evenings (2024-10-08) by Alan Hollinghurst (UK, 1954- )

A new Hollinghurst is always something to look forward to — he hasn’t exactly been cranking them out. This is his seventh novel since he started with The swimming-pool library in 1988, and it’s been seven years since The Sparsholt affair.

Our evenings takes us back to something like the structure of The line of beauty, with an outsider granted a glimpse into the world of English privilege over the shoulders of a grand family who take him in. We follow the career of gay, mixed-race actor David Win from his teens in the early 1960s through to Covid and Brexit. In the background we follow his friendship with the wealthy Mark and Cara Hadlow, who have endowed the scholarship that allows David to progress from a modest Home Counties background via public school and Oxford into the world of seventies avant-garde theatre. And we see the parallel advance of the Hadlows’ dreadful son Giles, who emerges (to the horror of his sophisticated parents) as a high-profile figure on the philistine, eurosceptic Tory right.

As you would expect, there’s a lot of beautiful detail along the way, revealing all kinds of fascinatingly complicated nuances in the development of English society over the last sixty years, including a delightfully unexpected dive into the genteel lesbian underground of sixties small-town Buckinghamshire. Of course there’s also a lot of very interesting stuff about acting and the theatre. Besides the inevitable Shakespeare we also get into modern playwrights, real and invented, and of course Racine, whose plays Hollinghurst has translated.

A true delight, even if it does turn out to be another book about the nastiness of now.

Our Evenings (2024-10-08) by Alan Hollinghurst (UK, 1954- )

A new Hollinghurst is always something to look forward to — he hasn’t exactly been cranking them out. This is his seventh novel since he started with The swimming-pool library in 1988, and it’s been seven years since The Sparsholt affair.

Our evenings takes us back to something like the structure of The line of beauty, with an outsider granted a glimpse into the world of English privilege over the shoulders of a grand family who take him in. We follow the career of gay, mixed-race actor David Win from his teens in the early 1960s through to Covid and Brexit. In the background we follow his friendship with the wealthy Mark and Cara Hadlow, who have endowed the scholarship that allows David to progress from a modest Home Counties background via public school and Oxford into the world of seventies avant-garde theatre. And we see the parallel advance of the Hadlows’ dreadful son Giles, who emerges (to the horror of his sophisticated parents) as a high-profile figure on the philistine, eurosceptic Tory right.

As you would expect, there’s a lot of beautiful detail along the way, revealing all kinds of fascinatingly complicated nuances in the development of English society over the last sixty years, including a delightfully unexpected dive into the genteel lesbian underground of sixties small-town Buckinghamshire. Of course there’s also a lot of very interesting stuff about acting and the theatre. Besides the inevitable Shakespeare we also get into modern playwrights, real and invented, and of course Racine, whose plays Hollinghurst has translated.

A true delight, even if it does turn out to be another book about the nastiness of now.

29dchaikin

>28 thorold: popular with Booker readers. Although some readers find it a bit long. I’m happy to see your review.

30thorold

Another recent publication. A library book this time, but I think I’m going to end up buying a copy, if only for the bibliography… Mary Kemperink is emeritus professor of Dutch literature in Groningen.

Anders dan de anderen: homoseksualiteit op het snijvlak van literatuur en medische wetenschap (2024) by Mary Kemperink (Netherlands, 1951- )

Reading has long been an important way for lesbians and gay men to break through social isolation and explore our identities as part of a much wider community, within a historical continuity that stretches back to Plato and Sappho. There is a well-established canon of ”queer classics” that we all find our way into at some point, and in the last few decades that has been extensively written about by queer theorists, who have managed to add a lot more “forgotten” texts to the canon in the process.

Kemperink takes us through this canon, focussing on books written in French, German, English and Dutch between about 1830 and 1930, but she widens the perspective to put it into the context of other kinds of contemporary writings about homosexuality, looking in particular at medical texts, but she also takes into account pornography and mainstream sensational literature in which lesbian or gay characters appear, usually in a negative light, as criminals or degenerates. It’s especially interesting to see the strong parallels between the (often autobiographical) case-studies that are included in medical texts and the ways in which queer characters are portrayed in fiction. Clearly, doctors got a lot of their ideas about homosexuality from fictional stereotypes, whilst writers of fiction brought ideas from medical studies into their analyses of the characters in their books. Novels often came with endorsements from leading sexologists like Hirschfeld and Krafft-Ebing, and frequently contained doctor characters who either display the ignorant intolerance of the medical mainstream or quote the enlightened ideas of the sexologists.

Whilst quite a lot that was written about queer characters was written by people with no first-hand knowledge (in particular, the very substantial category of lesbian fiction written by men…), it’s interesting how even sympathetic writers who did come out of the milieu they were writing about tended to stick to clichés like the effeminate gay man and the mannish lesbian to fit in with prevailing scientific theories. It’s rare that you get someone like Balzac’s Vautrin who doesn’t fit into any of those neat models.

A fascinating study, and — in passing — a useful reminder of how little of the real ”queer canon” was available in English before about 1960. Censorship laws meant that you pretty much had to be able to read French or German if you wanted to see books in which gay or lesbian characters were presented in a sympathetic light. And even German wasn‘t much help if you wanted to read books by and about women.

Anders dan de anderen: homoseksualiteit op het snijvlak van literatuur en medische wetenschap (2024) by Mary Kemperink (Netherlands, 1951- )

Reading has long been an important way for lesbians and gay men to break through social isolation and explore our identities as part of a much wider community, within a historical continuity that stretches back to Plato and Sappho. There is a well-established canon of ”queer classics” that we all find our way into at some point, and in the last few decades that has been extensively written about by queer theorists, who have managed to add a lot more “forgotten” texts to the canon in the process.

Kemperink takes us through this canon, focussing on books written in French, German, English and Dutch between about 1830 and 1930, but she widens the perspective to put it into the context of other kinds of contemporary writings about homosexuality, looking in particular at medical texts, but she also takes into account pornography and mainstream sensational literature in which lesbian or gay characters appear, usually in a negative light, as criminals or degenerates. It’s especially interesting to see the strong parallels between the (often autobiographical) case-studies that are included in medical texts and the ways in which queer characters are portrayed in fiction. Clearly, doctors got a lot of their ideas about homosexuality from fictional stereotypes, whilst writers of fiction brought ideas from medical studies into their analyses of the characters in their books. Novels often came with endorsements from leading sexologists like Hirschfeld and Krafft-Ebing, and frequently contained doctor characters who either display the ignorant intolerance of the medical mainstream or quote the enlightened ideas of the sexologists.

Whilst quite a lot that was written about queer characters was written by people with no first-hand knowledge (in particular, the very substantial category of lesbian fiction written by men…), it’s interesting how even sympathetic writers who did come out of the milieu they were writing about tended to stick to clichés like the effeminate gay man and the mannish lesbian to fit in with prevailing scientific theories. It’s rare that you get someone like Balzac’s Vautrin who doesn’t fit into any of those neat models.

A fascinating study, and — in passing — a useful reminder of how little of the real ”queer canon” was available in English before about 1960. Censorship laws meant that you pretty much had to be able to read French or German if you wanted to see books in which gay or lesbian characters were presented in a sympathetic light. And even German wasn‘t much help if you wanted to read books by and about women.

31thorold

When I was in the library on Friday returning >30 thorold:, I couldn’t help spotting a recent reprint of one of the “forgotten” books Kemperink discusses…

Pijpelijntjes (1904, 1991) by Jacob Israël de Haan (Netherlands, 1881-1924)

Jacob de Haan was a colourful figure, notable in all kinds of different fields — he was a Marxist, a pioneer of semiotics, a campaigner on behalf of political prisoners, and when he moved to Palestine after the First World War his journalistic work, critical of hardline Zionism, led to him becoming the victim of a high-profile political assassination by Jewish terrorists. But he was also a poet and the author of two of the first explicitly gay-themed novels to appear in Dutch, Pijpelijntjes (1904) and Pathologiën (1908).

Pijpelijntjes is set in the working-class Amsterdam neighbourhood De Pijp, where narrator Corrie — a young journalist — and his boyfriend Hans — a medical student — are sharing a furnished room. The two of them clearly have a strong emotional and physical bond, but there are also signs of impending fracture in the relationship: Hans has outbursts of anger and (sadistic) cruelty, and disappears for days at a time, whilst Cor finds himself distracted by the boys he sees on the street. But Cor is also getting more and more deeply involved in the life of their landlady Mrs Mens (Dutch for “person”!) and the complicated social networks of a neighbourhood where many of the men are in jail for one reason or another and most of the women seem to be looking after children of rather miscellaneous parentage.

The novel is written in a working-class flavour of high modernist style — all in Amsterdam dialect, and full of fragmented sentences linked by ellipses. The same sort of thing that James Joyce was experimenting with at the time, but hadn’t published yet, so it must have seemed very bleeding-edge to contemporary readers. There isn’t much explicit plot, we are there to observe the trivial details of real people’s lives, and it’s all quite fascinating. We get to look over Cor’s shoulder at neighbourhood disputes, tea-parties, prison visits, medical emergencies and police raids, and to get a feel for how ordinary people in this kind of neighbourhood were living in 1904, whilst the breakdown in the relationship between Cor and Hans goes on in the background.

It’s also fascinating in the context of the times that this is a novel about a gay relationship in which neither the authorial voice nor the other characters in the book ever get involved in homophobia. By a bit of authorial sleight of hand de Haan avoids this ever becoming an issue, and thus forces his readers to look at the relationship in the same way as if it were a flawed relationship between a man and a woman. It is a trick, of course: we can presume that they wouldn’t have had it so easy in real life, but it works.

The first edition of the novel caused a certain amount of fuss, unsurprisingly — it was especially problematic because one of the characters bore rather a strong resemblance to the book's dedicatee, the writer and doctor A Aletrino, whose friends colluded to buy up and destroy almost the whole publishing run. De Haan quickly brought out a second edition where he had revised the text slightly to remove the dedication and disguise the character a little better. The reprint I read was based on this second edition.

Pijpelijntjes (1904, 1991) by Jacob Israël de Haan (Netherlands, 1881-1924)

Jacob de Haan was a colourful figure, notable in all kinds of different fields — he was a Marxist, a pioneer of semiotics, a campaigner on behalf of political prisoners, and when he moved to Palestine after the First World War his journalistic work, critical of hardline Zionism, led to him becoming the victim of a high-profile political assassination by Jewish terrorists. But he was also a poet and the author of two of the first explicitly gay-themed novels to appear in Dutch, Pijpelijntjes (1904) and Pathologiën (1908).

Pijpelijntjes is set in the working-class Amsterdam neighbourhood De Pijp, where narrator Corrie — a young journalist — and his boyfriend Hans — a medical student — are sharing a furnished room. The two of them clearly have a strong emotional and physical bond, but there are also signs of impending fracture in the relationship: Hans has outbursts of anger and (sadistic) cruelty, and disappears for days at a time, whilst Cor finds himself distracted by the boys he sees on the street. But Cor is also getting more and more deeply involved in the life of their landlady Mrs Mens (Dutch for “person”!) and the complicated social networks of a neighbourhood where many of the men are in jail for one reason or another and most of the women seem to be looking after children of rather miscellaneous parentage.

The novel is written in a working-class flavour of high modernist style — all in Amsterdam dialect, and full of fragmented sentences linked by ellipses. The same sort of thing that James Joyce was experimenting with at the time, but hadn’t published yet, so it must have seemed very bleeding-edge to contemporary readers. There isn’t much explicit plot, we are there to observe the trivial details of real people’s lives, and it’s all quite fascinating. We get to look over Cor’s shoulder at neighbourhood disputes, tea-parties, prison visits, medical emergencies and police raids, and to get a feel for how ordinary people in this kind of neighbourhood were living in 1904, whilst the breakdown in the relationship between Cor and Hans goes on in the background.

It’s also fascinating in the context of the times that this is a novel about a gay relationship in which neither the authorial voice nor the other characters in the book ever get involved in homophobia. By a bit of authorial sleight of hand de Haan avoids this ever becoming an issue, and thus forces his readers to look at the relationship in the same way as if it were a flawed relationship between a man and a woman. It is a trick, of course: we can presume that they wouldn’t have had it so easy in real life, but it works.

The first edition of the novel caused a certain amount of fuss, unsurprisingly — it was especially problematic because one of the characters bore rather a strong resemblance to the book's dedicatee, the writer and doctor A Aletrino, whose friends colluded to buy up and destroy almost the whole publishing run. De Haan quickly brought out a second edition where he had revised the text slightly to remove the dedication and disguise the character a little better. The reprint I read was based on this second edition.

32FlorenceArt

>31 thorold: Fascinating!

33LolaWalser

Very cool, will be looking for de Haan.

34rv1988

>30 thorold: This is fascinating, and I hope it will be available in translation some day.

35thorold

>34 rv1988: I hope so, but I’m not optimistic. It’s certainly true that none of the books about this topic I’ve read in English covers anything like the same range even of French and German writing. As a rule it doesn’t go much beyond Gide and Colette.

A random Very Short Introduction that caught my eye in passing:

Bestsellers: A Very Short Introduction (2007) by John Sutherland (UK, 1938- )

The main strength of the Very Short Introduction series is in giving the “intelligent outsider” a way into a subject that you normally wouldn’t dare to venture into, because of the way it is surrounded by impenetrable-looking fortifications of theory or technical jargon. Popular fiction isn’t like that: by definition, it’s a subject that all of us (with the possible exception of serious literary scholars) know something about, but it defeats our grasp because of its vast geographical, chronological and generic scope. None of us has enough time to read every popular Victorian novel, every pulp detective story, every Western, every Mills & Boon romance, every paperback with a half-naked woman on the cover and the whole canon of science-fiction… And, of course, even an author who has written extensively about the history of popular fiction can’t hope to cover all that in just over a hundred pages.

Sutherland gives us a brief overview of the commercial history of publishing in the UK and US and sketches out the difficulty of defining what we mean by “bestseller” — is it the book that has sold most copies in a week or month, or the book with the biggest long-term sales (over a five-hundred-year period, The Pilgrim’s Progress has outsold Dan Brown), or the author with the biggest total sales (Agatha Christie, whose individual titles rarely got into the charts)? Do we sample or count real point-of-sale totals? Do we count children’s books separately or in the same category as mainstream novels? What do we do about utility items like The Highway Code, always a big seller in the UK Market?

Sutherland also takes us on a lightning tour of some of the salient bestsellers of the 20th century in the US and the UK, which is entertaining and occasionally illuminating, but if you’re looking for an analysis of what makes a book a popular success you won’t find it here. Bestsellers are, with hindsight, always in tune with the spirit of the times in which they have their greatest success (occasionally long after their initial publication, as in the case of The Forsyte Saga or Lady Chatterley), but there’s no sure way of knowing in advance what that’s going to be. (Sutherland doesn’t say so, but of course bestsellers themselves are one of the most important cultural elements we look to in defining the “spirit of the times” when we look back.) Even sequels and blatant clones of earlier successes don’t always hit the mark.

A fun read, but less useful than some of the other VSI’s.

A random Very Short Introduction that caught my eye in passing:

Bestsellers: A Very Short Introduction (2007) by John Sutherland (UK, 1938- )

The main strength of the Very Short Introduction series is in giving the “intelligent outsider” a way into a subject that you normally wouldn’t dare to venture into, because of the way it is surrounded by impenetrable-looking fortifications of theory or technical jargon. Popular fiction isn’t like that: by definition, it’s a subject that all of us (with the possible exception of serious literary scholars) know something about, but it defeats our grasp because of its vast geographical, chronological and generic scope. None of us has enough time to read every popular Victorian novel, every pulp detective story, every Western, every Mills & Boon romance, every paperback with a half-naked woman on the cover and the whole canon of science-fiction… And, of course, even an author who has written extensively about the history of popular fiction can’t hope to cover all that in just over a hundred pages.